Should I avoid salt?

The media loves to polarise debates – anything to get a new headline – and there’s nothing like the constant to-ing and fro-ing about whether certain foods are good or bad for us. But where do the experts truly disagree – and how much do they actually agree on?

Michael Mosley talks to pairs of researchers who are traditionally pitted as having opposite viewpoints, to see where the disagreements truly lie – and where they are merely a concoction of media reporting.

Does cutting back on salt prevent stroke and heart attack? Professor Graham MacGregor explains why he thinks so

Prof Graham MacGregor tells Michael Mosley why he campaigns for stronger cuts in salt.

Does cutting back on salt prevent stroke and heart attack? Professor Hugh Tunstall-Pedoe thinks the evidence isn't convincing

Prof Hugh Tunstall-Pedoe explains the lack of convincing evidence in the salt debate.

One of the best-known public health messages is to cut back on salt (sodium chloride) in order to avoid high blood pressure and heart problems. Most of us consume about nine grams of salt a day, yet the current government advice is that we should be cutting this down to just six grams a day - about a teaspoon, or the amount found in a single bacon sandwich.

But how strong is the evidence to back this message up? And how do we end up with such disparate media headlines on a debate which has been around for more than half a century?

The first time salt was blamed for hypertension (high blood pressure) was in 1960 in a publication which has since been roundly criticised. The researcher, Lewis Dahl, compared the health and salt intake of different ‘races’ to show a correlation between poor health and high salt – but he was extremely selective in the data that he chose to publish in order to make a case for his own theory.

He also picked up on research from the 1940s showing that a diet of rice and peaches (which therefore had an extremely low sodium content) could reduce high blood pressure – and as a result, a public health message began.

However, researchers called for better evidence to back up the message and in the 1980s, a huge international study called INTERSALT was set up to examine the relationship and settle the matter once and for all. It took them a long time to agree on a protocol which every centre would use to assess sodium intake and blood pressure.

In Scotland at the same time (1984), the Scottish Heart Health Study was starting up (trying to get to the bottom of Scotland’s high Cardio Vascular Disease rates). They decided not to wait for INTERSALT to decide on a protocol (as they were looking at a whole range of other factors), and went ahead starting to collect data.

In 1988, the British Medical Journal finally carried the results of both INTERSALT and the Scottish Health Study’s findings on the link between salt and hypertension and cardiovascular disease:

The INTERSALT results have been a source of controversy since they were published in 1988. Researchers argue as to whether INTERSALT’s results were positive or negative and the debate has often become heated. Some statisticians have criticised cherry-picking the data that supports a reduction in salt while ignoring data that points in the opposite direction.

Almost all experts advocate cutting back on salt as there is no accepted risk to this advice – an Italian study that appeared to show a reduction in salt being potentially harmful is now generally accepted as flawed. However, in April 2014 paper by Dr Niels Graudal apparently showed a higher mortality at both ends of the salt intake spectrum. He has claimed that most people are within the ‘safe’ limits and shouldn’t cut back further as too low an intake could be equally as harmful as too much.

The issue is not as clear-cut as the public health messages might lead us to believe, so what should we all do?

The Issues

Both agree that we should all cut back on our sodium intake (from table salt), and increase our potassium intake (from eating more fruit and vegetables). However, Prof Tunstall-Pedoe believes that the evidence to support a link between sodium intake and cardiovascular problems is weak – much weaker than the evidence for the benefits of increasing potassium intake, reducing alcohol intake or reducing weight, for instance.

He believes that cutting back on salt will do us no harm and might be beneficial so we should use less but he doesn’t believe that the scientific case for cutting salt as a direct way of reducing blood pressure has been made. He thinks the science is still controversial and there is not a consensus, whilst Prof MacGregor believes that the link between salt and cardiovascular problems is unassailable and that if we all cut back, thousands of premature deaths could be avoided in the UK.

Related Links

Our contributors

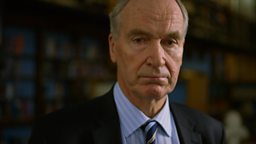

Professor Graham MacGregor

Professor Graham MacGregor is Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine. He has spent over 20 years investigating the effect salt has on blood pressure and he also leads an action group that campaigns for a reduction of salt intake in the U.K.

Profile:

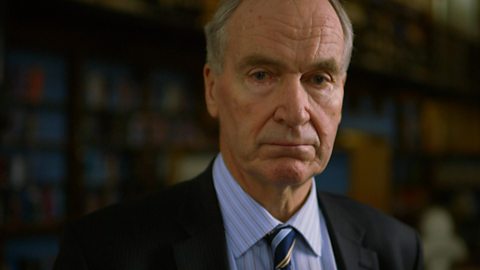

Professor Hugh Tunstall-Pedoe

Hugh Tunstall-Pedoe is Professor of Cardiovascular Epidemiology at the University of Dundee. He's spent over forty years researching the causes of disease and his findings on blood pressure are at odds with the familiar public health message about salt. He was also the lead researcher on the Scottish Heart Health Study.

Profile: