Should I worry about Seasonal Affective Disorder?

For many of us, winter will have some kind of impact on the way we feel: in a survey in 2014 over half the participants reported that they felt worse in the darker months compared to the summer. However, for about 5% of the UK population, the winter can bring about more than just a low mood – it can cause serious depression which has a huge impact on sufferers’ lives. So what exactly is SAD, how do you know if you have it and what can you do about it?

What is SAD?

Seasonal Affective Disorder was identified in the 1980s by Prof Norman Rosenthal, a South African psychiatrist working in the United States, and in 1987 the American Psychiatric Association recognised it as a mental health condition.

SAD is a recurring winter depression which in most cases is brought about by the shorter days and the amount of daylight we are exposed to. This is because light doesn’t just allow us to see, but is actually a trigger for many processes in the body.

Michael met , professor emerita at the Centre for Chronobiology, University of Basel, Switzerland, who revealed that there are two major theories to explain why some people get SAD, in addition to probable genetic vulnerability.

- Hibernation type effects: humans may respond to the shortening of days in winter with the appropriate bodily changes that were once important for survival (rather like hibernation in some species.)

- The body clock: a particular photoreceptor in the eye detects light and helps to set our body clock, which in turn controls our mood and when we feel awake or sleepy. In winter, when we might not be getting enough daylight, this can throw our rhythms out of synch and lead to the kind of symptoms that characterise ‘the winter blues’ or SAD.

What are the symptoms of SAD?

SAD is not necessarily something you have or do not have – it’s better described as a spectrum. Many of us may experience some of the symptoms to a greater or lesser degree, while a small percentage of people will be affected severely.

The main characteristic of SAD is that the symptoms are recurrent in autumn and winter and improve in spring and summer (hence the name).

Many of the symptoms are similar to non-seasonal depression including:

- A lingering low mood that persists

- Loss of enjoyment or interest in normal everyday activities

- Being irritable

- Having feelings of despair, guilt and worthlessness

- Lacking in energy and feeling sleepy during the day

Other symptoms include:

- Sleeping for longer than normal

- Finding it hard to get up in the morning

- Craving carbohydrates and gaining weight

It’s when these symptoms start to have an impact on our day-to-day lives that we need to see a doctor.

How is a diagnosis made?

Like most psychiatric conditions, questionnaires are used as screening tools for SAD.

Michael completed a Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (SPAQ) which looks at how the seasons may change our mood and behaviour.

Interestingly, Michael scored higher than average on this, revealing that he is affected by the seasons, but not to the extent that it has an impact on his day to day life or causes seasonal depression.

The results of this questionnaire are not a diagnosis, but they can indicate there may be a problem and further assessment by a psychiatrist may be required.

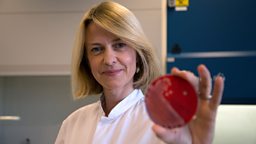

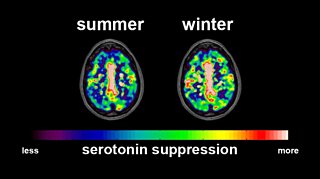

Unfortunately there are no physical tests for diagnosis, but work by from Copenhagen University Hospital has looked at the brains of those who suffer from SAD using a technique called PET (Positron Emission Tomography).

She examined volunteers with and without SAD in both summer and winter and compared the results of the scans to the severity of their symptoms.

In particular she was interested in a chemical in the brain called serotonin, which is related to mood.

Brenda found that in summer all the volunteers managed their serotonin levels in the same way, whether they suffered from SAD or not. However, in winter, the brains of SAD sufferers seemed to be being deprived of serotonin.

What’s more there was a link between the severity of the SAD symptoms and the amount of serotonin being removed from the parts of the brain that needed it.

How can SAD be treated?

Like with any depression, there are medications and tailored psychotherapies available.

Some sufferers benefit from cognitive behavioural therapy specialising in SAD.

However, one of the most widely used and successful treatments is light therapy.

This can be as simple as getting out for a 30 minute walk in the morning, having breakfast by a window, or exposing yourself to light each morning with a specially designed light box.

While light boxes are not available on the NHS, they are recommended as a course of treatment by the British Association of Psychopharmacology and research groups around the world.

What should I look for in a light box?

- To be effective, a SAD Lamp must provide at least 10,000 lux (a measure of illuminance) at a fixed distance. For example if a product says 10,000 lux at 30cm this is the maximum distance the lamp can be from you to make sure you are getting enough light.

- In general most lamps will recommend they are used for 30 minutes in the morning to be most effective, but longer times may be necessary for some people.

- If a lamp is fluorescent it should have a diffusing screen to filter out UV light

- Lamps should have off white coloured light – blue or bluish lamps have no known advantage.

- Always follow the instructions from your supplier.

Related links

Note about the questionnaire

The Seasonal Patient Assessment Questionnaire to which we link is an example that provides further information on the questions Michael answered in . If you are interested in assessing your own symptoms, you should consult your GP; the Trust Me, I’m a Doctor team cannot assess your responses.