Are ‘antioxidant-rich’ products good for me?

The term ‘antioxidant’ has become a marketing buzzword, with juices and smoothies particularly often branded ‘antioxidant-rich’, and some fruit and veg have been rebranded as ‘superfoods’, usually because they are said to be especially rich in them.

Antioxidants are chemicals which prevent ‘oxidation’ – a chemical reaction which happens all the time (it makes iron rust, and apples go brown). Inside our bodies, antioxidants are often said to ‘neutralise’ or ‘mop up’ free radicals.

Free radicals are naturally produced by your body as part of the range of chemical reactions in each and every cell. Free radicals are known to damage the DNA and other apparatus in our cells – and this, in the long term, can to lead to a host of diseases such as cancer. One theory of how we age has long been that it is caused by an accumulation of this damage by free radicals.

The theory of antioxidant benefit, then, is that consuming extra antioxidants can reduce cell damage by free radicals and so benefit our health. We wanted to put various stages of this well-marketed theory to the test.

How strong is the antioxidant power of ‘antioxidant smoothies’?

We went shopping for juices and smoothies which proudly displayed their antioxidant credentials.

- A fresh ‘Superfruit Smoothie’ from a juice bar

- Two brands of ‘Antioxidant’ smoothie

- A brand of ‘Superfood’ Smoothie

- Three different kinds of orange juice from concentrate (with and without ‘bits’).

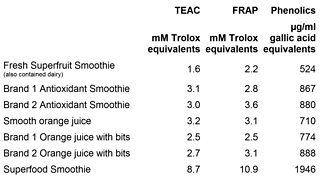

Dr Kirsten Brandt from Newcastle University carried out the tests using two measures for antioxidant power:-

- Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC)

- The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP)

The results

Surprisingly, the freshly prepared Superfruit smoothie had the lowest anti-oxidant count, but its dairy content may have been the cause.

The two smoothies that were labelled “Antioxidant” had very similar levels to the orange juices we tested. The Superfood smoothie, however, had three times more than any other. It was made from red berries, but also had added vitamins, such as vitamin C and E.

Vitamin C is a powerful antioxidant – it is found in many fruit and veg naturally, and is often added to juices after processing to help stop them going brown (oxidising). Vitamins A and E are also antioxidants, and so commercial juices and smoothies with these vitamins added can have high antioxidant capacity as a result.

But what does this do to us when we drink it?

What do antioxidant smoothies do to us?

We wanted to find out whether drinking a smoothie high in antioxidants had any effect on the antioxidant levels in the body.

Ten healthy volunteers (BMI between 18.5-30) were asked to avoid foods containing antioxidants for 48 hours before the experiment started and for 24 hours afterwards. This included fruit, vegetables and whole grain products, coffee and tea, beer and wine.

Each volunteer was asked to drink 360 mls of a smoothie that was advertised as being rich in antioxidants.

A blood sample was taken before the experiment and then at intervals for 24 hours. Each sample was analysed for antioxidant concentration and for blood sugar levels.

A urine sample was also taken before and after the experiment started.

The results

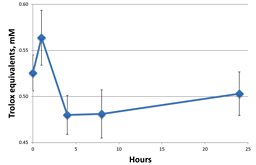

Plasma TEAC

After an initial rise in the antioxidant status after one hour, the concentrations then fell below the baseline. By the time the experiment had finished (24 hours), the level of antioxidants in the volunteers’ blood was only just back to normal.

The urine samples showed no significant change in the level of antioxidants.

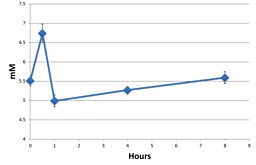

Plasma glucose

The volunteers’ blood showed a sharp spike in blood glucose in the first hour which then returned to baseline over a period of eight hours.

What does this mean?

The antioxidants from the smoothie seemed to be taken into the volunteers’ blood quickly. However, the body has a mechanism to deal with such a sudden rise, and extra antioxidants in the blood are removed quickly from the blood. This is an example of a process called homeostasis, where the body works to return its antioxidant levels to the ideal. The same happened to the sugar from the smoothie – it caused a spike, and then a sudden dip afterwards to below baseline.

So even if the antioxidants we take in our diet do neutralise free radicals, drinking extra can’t be neutralising more, as, for the majority of the time afterwards, there is less antioxidant power in the blood.

However the urine samples didn’t show that the body had flushed out extra antioxidants from the smoothie, so the body has probably converted the additional extra antioxidants into other compounds that don’t have antioxidant activity.

The blood sugar samples show a sharp spike, similar to what you might expect from drinking a soft drink. This is little surprise, as the smoothie they drank contained 47 grams of sugar – almost 12 teaspoons. By comparison a 330 ml can of coke contains 9 teaspoons of sugar.

So are antioxidant-rich foods and drinks good for me?

The old ‘free radical theory of aging’ is now thought to be wrong. Instead, it is thought that free radicals are vital signals within our cells to stimulate the body’s own repair and regeneration mechanisms. For example, in one experiment, high doses of antioxidants (in the form of vitamin C) were given to people doing exercise training. Those who were taking the antioxidants failed to get fitter as a result of the training, thought to be because the antioxidants neutralised the free radicals that were signalling that the body respond to the exercise.

This does not go against the fact that eating fruit and vegetables is good for us – it’s just that this benefit is not now thought to be down to their antioxidant chemicals. Juices and smoothies should be consumed sparingly, because of the high levels of very readily accessible sugar they contain. While they can serve as a component of a healthy diet, it should only be in moderation.

Related Links

Responses from juice manufacturers

A Naked Juice spokesperson said:

A considerable body of scientific evidence supports the important role that fruits and vegetables and juices can play in a healthy balanced diet and Government dietary advice recommends that we consume at least 5 portions of fruit and veg a day. Only 30% of adults and 10% of children comply with this recommendation. Juices and smoothies are therefore a convenient way to help people move towards this recommendation and consumers of these products are 70% more likely to achieve 5 A Day. Juices and smoothies are an important source of vitamin C and other micronutrients for consumers; the National Diet and Nutrition Survey has shown that juice provides 52% of vitamin C, 13% folate and 11% potassium intake.

A spokesperson for Innocent Smoothies said:

Here at innocent we’re all about making it easier for people to do themselves some good. All our juices and smoothies help our drinkers get more fruit and veg into their diet (something the WHO and other major health organisations recommend we all do*), at a time when only a third of the UK population are getting their 5 a day.

Back in 2014, we added a group of smoothies to our range that are a blend of fruit and veg, with the addition of seeds, botanicals, vitamins and minerals. These offer drinkers delicious tasting smoothies that come with the good stuff from fruit and veg plus some functional benefits. The smoothie you reference includes kiwi, lime, wheatgrass, flax seeds, vitamin C, E and Selenium.

We would expect your measure of ‘antioxidant power’ to be similar for juices and smoothies because it is registering overall antioxidant activity rather than specific antioxidant function. Different fruits vary in their precise antioxidant function and we are confident that the vitamin and minerals in our antioxidant recipe contribute to the protection of cells from oxidative stress (a claim we are supported in making by European Regulation (EC) 1924/2006 Nutrition and Health Claims).

It’s difficult for us to comment further on the findings of your study, as we are not aware of the methods and approach you have taken, or the sample of participants for the study. In only measuring the Ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) and Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) might it be possible that you are missing the other two measures of Oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) and Hydroxyl radical antioxidant capacity (HORAC)? The experts we work with in this field advise us to look at all four measures so perhaps there are other measurable effects not included in your study?

Our research reviews conclude that the benefits of consuming fruit & vegetables (and therefore their antioxidants) become apparent in health markers over a period of years rather than hours so are hard to reflect in a typical laboratory study.

With only one third of the UK population are getting their 5 a day, we are proud of the contribution our juices and smoothies make to helping people get more fruit and veg into their diet.