The concept and development of organised police forces

- Rapidly rising crime rates as a result of population growth and urbanisation in the 18th century pushed traditional methods of law enforcement beyond their ability to work effectively.

- Local experiments were conducted to find more effective alternatives.

- The increasing threat of protests and potential revolution also convinced the authorities that more needed to be done to enable enforcement of the law.

Organised policing in the 18th-century

By the 18th century it was becoming increasingly clear that the existing system of policing was not effective. The crime rate was rising and new crimes were emerging. Justice of the Peace Someone responsible for maintaining law and order in a county. Often abbreviated to JP. (JPs) were often corrupt. Watchmen were usually ineffective and constables often resented the requirements of their job.

Increases in population and the growth of towns meant it was difficult for unpaid amateurs to maintain law and order. Unofficial policemen, sometimes called thief takers, began to make profits by capturing criminals. They also negotiated the return of stolen goods to owners and claimed rewards. One of these thief takers was called Charles Hitchin. His accomplice, Jonathan Wild, was later nicknamed the âThief Taker General of Great Britain and Irelandâ. He appeared to voluntarily police the streets of London, handing over criminals to the authorities and negotiating the return of the goods for profit. However, he and his men were actually behind most of the theft in the area.

Some pioneers began developing the concept of an organised, paid police force in London.

The Fielding brothers

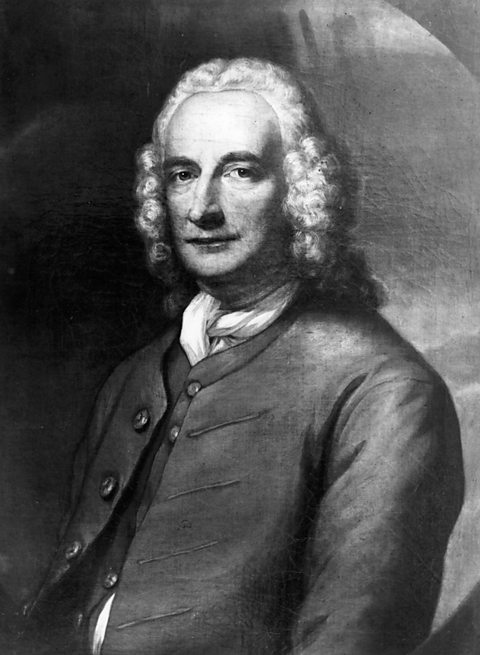

Half-brothers Henry and John Fielding were magistrateA judge who hears cases in court. at Bow Street Court in London. Henry became chief magistrate at the court in 1748. He wrote a report about the rise in crime called An Enquiry into the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers and Related Writings, which was published in 1751. His report stated that Londonâs crime rate was due to people expecting an easy life and resorting to crime rather than work, corruption in the government and the ineffective policing system.

Henryâs motto was âquick notice and sudden pursuitâ. He believed in using the knowledge of the public and placed adverts in newspapers asking people to help him. This was a similar approach, albeit using a different method, to earlier approaches that involved the community.

Henry and his half-brother John set up a force of paid constables who patrolled London, called the Bow Street Runners. This began with six men, who were trained, paid and worked as full-time officers. At first these men were paid from a government grant, but they also got rewards from catching suspects in the same way as thief takers. By 1800, there were 68 Bow Street Runners in London.

Organised policing in the 19th-century

By the start of the 19th century, there was increasing support for the concept of a professional, state-funded, full-time police force. In 1800, Glasgow adopted a scheme in which constables and watchmen were organised into a force to protect the city. However, the most significant turning point came when Sir Robert Peel, ±«Óătv Secretary, supported the idea of the government taking responsibility for organising policing.

Peel set up the first uniformed and organised police force in 1829. He believed in policing by consent. This is the idea that ordinary people will trust the police to act honourably and will be held accountable for their actions.