Enforcing law and order in Saxon and medieval times

Communal and family responsibility

In Saxon and medieval times, people policed their own community. Men were arranged into groups of ten called tithings. If a crime was committed in the tithing, it was everyone's responsibility to bring the person to justice.

If a crime was committed and the members of the tithing were not there to deal with it, the victim could shout for help. This was known as the âhue and cryâ and anyone who heard it was supposed to come and help. If this did not work, then the local royal official (known as the shire reeve) would create a posse of armed men to hunt for the criminal.

Every year, in each area, two chief constables were appointed to supervise law and order. Every parish had its own constable, who made sure that the law was being enforced properly. These constables were all volunteers and had to perform their duties as well as doing their normal job.

Saxon courts

There was a simple hierarchy of courts in Saxon times. Its influence spread as kings took control of more of the country. Kings would make judgements in cases that involved their lords. Shire courts were established in the counties to enable local lords to make judgements about serious crimes committed in their area. Each shire was divided into hundreds and each hundred had its own court, which dealt with the less serious cases brought forward by the tithings. All landowners could also settle minor disputes in their own private courts.

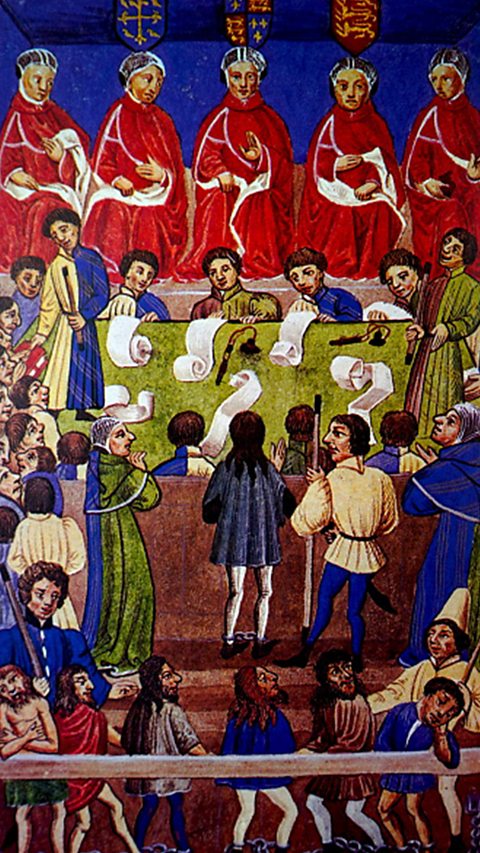

Courts in the medieval era

The Saxon system of courts was developed further in the medieval era as the king, the Church and local landowners all came to play more of a part in administering justice.

Royal courts like the Kingâs Bench heard the most serious cases, although the people on the jury usually came from the accused personâs own community. In 1293 Edward I made a change to this system. He ordered royal judges to visit every county several times a year to hear serious cases in the area in which they were committed. These were called county assizes and they continued until 1971.

Church courts were overseen by ordained members of the Church. These dealt with moral offences such as missing a church service, being drunk and committing adultery. They also sometimes dealt with specifically religious offences, such as not knowing the words of the Lordâs Prayer.

The local bishop would pass judgement after hearing the evidence, although their punishments tended to be less severe than those passed in the ordinary courts. People accused of crimes would therefore often claim sanctuary from local justice in a church. The local priest would then hear the case and pass judgement on it.

As the importance and powers of local landowners were increased by the feudal systemA term used by historians to describe the hierarchical organisation of medieval society into different groups based on people's roles. The king was at the top of the system with the most power and peasants were at the bottom. imposed by the Normans, manor courts took over the job of administering justice in local areas. The local feudal lord, or a steward representing him, would make judgements about minor offences and local disputes with the help of a jury drawn from the local community. These courts were the focus of the justice system in the medieval era, although by 1500 a lot of this work had been taken over by Justice of the Peace Someone responsible for maintaining law and order in a county. Often abbreviated to JP. A parallel system was also set up for towns. These were known as borough courts. They were run by inhabitants of the town who had lived there for at least a year.

Policing in medieval times

County coroners were appointed after 1190. They enquired into violent or suspicious deaths, with the support of a jury of local people.

After 1250, villages started to appoint constables in each village to monitor law and order. These were leading villagers, who would take the role for one year. The role was unpaid and the constable would lead the hue and cry as well as carry out other responsibilities.

Trials before 1500

Royal judges travelled around the country dealing with serious cases. County courts were set up with Justices of the Peace (JPs), also known as magistrates, hearing cases. JPs were usually the main local landowners. The role was unpaid. Each village or manor still had a manor court, held by the local lord or landowner for minor cases.