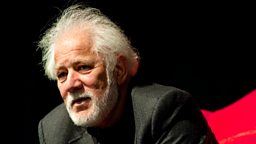

Kazuo Ishiguro: The giant awakens

19 February 2015

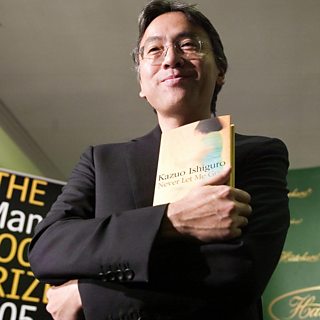

Readers of Kazuo Ishiguro are used to waiting a long time for his next novel. The first six - from A Pale View of Hills in 1982 to in 2005 - were published at intervals of four or five years. A decade has passed between the last of those fictions and the publication early next month of his seventh novel, The Buried Giant. MARK LAWSON looks back at a lengthy literary career.

The publication gaps are mainly due to Ishiguro being a meticulous and deliberative writer: even the short stories in his 2009 collection Nocturnes were, very unusually, written one by one for the book rather than having appeared in magazines over the years.

But, , the gestation of The Buried Giant was lengthened by the fact that he abandoned another novel. He always shows his work in progress to his wife, Lorna, and, on this occasion, she told him that the book - about a group of elderly vampires living in Europe - was unpublishable.

He turned instead to The Buried Giant, set in ancient Britain, where an elderly couple called Axl and Beatrice go on a journey in search of their son, who, for mysterious reasons, is no longer around.

Key lines spoken by husband to wife - “There’s a journey we must go on and no more delay” - have a phrasing and rhythm strongly reminiscent of the opening song in Stephen Sondheim’s recently-filmed musical Into the Woods.

And, while Ishiguro says that this overlap is coincidental or sub-conscious, The Buried Giant is, like Sondheim’s show, an attempt to create a modern fable or fairytale from traditional elements of the genre. In a story that draws on the legend of Gawain and the Green Knight, Axl and Beatrice live in a land stalked by ogres and dragons, although this is not strictly supernaturalism as Ishiguro is careful to include only creatures that people at the time believed to be real.

The writer’s choice of date and place this time continue another distinctive aspect of his fiction. Most novelists - for example, Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and Ian McEwan, with whom he was included on Granta’s Best Young British Novelists list in 1983 - set the majority of their stories in the country and the eras in which they are living at the time of writing. Not so with Ishiguro, who has never written a novel set in a recognisable present-day UK.

Admittedly, defining what should be Ishiguro’s natural fictional territory is complicated because he was born In Japan - in 1954, in Nagasaki, a city forever haunted as one of the targets of the atom bombs that ended World War II - but his family moved to Surrey in England when he was six, although he continued to speak Japanese at home.

As a result of this, although a UK passport holder and member of the Order of the British Empire, his work has always straddled two cultures. All of his fiction has been written in English; the Japanese he speaks and writes, he says in our interview, is a “child’s Japanese”, with none of the complications of vocabulary and additions of slang that usually occur in adult life, so that Japanese people look at him in surprise if they ever hear him speaking. His English prose, though, also has a foreign quality. The narration - in almost all the books, by a first-person monologuist - and the dialogue are formal, cautious, non-idiomatic. In our interview, the writer attributes this quality to the fact that, coming to the English language late, he approached it with care, wary of being caught out, and so some of this linguistic vigilance remains in him.

And, though 20th and 21st England have been his home, they have never been his fictional homeland. In the first two books - A Pale View of Hills and An Artist of the Floating World - elderly Japanese characters reminisce.

Ishiguro’s first novel set in England, The Remains of The Day - still his masterpiece, winning the Man Booker Prize for the author and eight Oscar nominations for the movie version - was written in the late 1980s but takes place between the 1930s and the ‘50s as Mr Stevens, an old butler, recalls professional and romantic disappointment.

His strangest and most audience-dividing novel, The Unconsoled (1995), is a Kafkaesque epic set in an unspecified European city, while When We Were Orphans (2000) is a detective novel that takes place in early 20th century China, and Never Let Me Go (2005) crosses genres by being a sort of historical science-fiction, played out in an alternative 1980s England at a school for children who have been raised to be organ donors.

So, by locating his latest novel in a very early Britain, Ishiguro extends his record of almost never having written about the world that was to be found outside the window of his study, always exploring the past of either people or a place. And the title - and organising metaphor - of The Buried Giant contain an explanation for this fascination with looking backwards.

The huge figure supposedly buried beneath the landscape stands for the disfiguring hidden histories that countries often ignore: notoriously in Japan, where the truth of the nation’s behaviour and defeat in the Second World War were rarely spoken of and deliberately not taught in schools, but also in Britain: one of the themes of The Remains of the Day is the Nazi sympathisers among the aristocracy in the 1930s.

Even at the end of the seventh novel, there is a strong sense that the buried giant is not yet slain and that in future novels - the next due in five to ten years time, if it gets past his wife’s editing pencil - he will return again to the past, somewhere between Surrey and Nagasaki.

is on ±«Óătv Four at 22:00 on Sunday 22 February 2015.

Readings

Ishiguro reads from 2015 novel The Buried Giant

Ishiguro reads from 1995 novel The Unconsoled

Ishiguro reads from 2015 novel The Buried Giant

-

![]()

Book at Bedtime on Radio 4 is featuring Kazuo Ishiguro's haunting novel of friendship, love and loss as part of its Dangerous Visions season.

-

![]()

Readings, interviews and features with Kazuo Ishiguro