A sanctuary for the endangered whale shark: Cenderawasih Bay

By Jess Webster, Junior Researcher on Seven Worlds, One Planet

Usually elusive and deep sea dwelling, nothing could have prepared me for their huge, gentle beauty.Seven Worlds Director, Lucy Wells

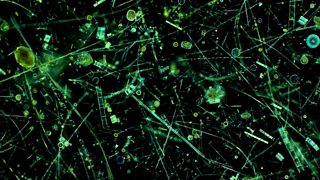

Roaming the world’s temperate and tropical oceans, the whale shark is the largest species of fish, feasting on an abundance of microscopic plankton as it cruises gracefully through the water. These ocean giants may live to be over 100 years old, but are facing a host of devastating threats across their range including overfishing of reef fish, coastal development, pollution and poaching.

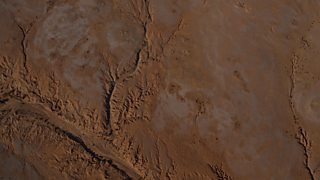

But in the pristine waters of West Papua, there is a different story. Here, whale sharks command an ancient respect and are able to safely gather in remarkable numbers, enjoying a rare moment of refuge as local fishermen treat them to an easy meal. To capture this extraordinary relationship, the Seven World’s team travelled deep into the heart of Indonesia to visit a special community of fishermen operating out of Cenderawasih Bay. For over two decades whale sharks have congregated at the bagans (fishing platforms) of these fishermen, where they are thrown handfuls of small, silverside baitfish - a gesture reflecting the fishermen’s positive attitude towards these majestic visitors. In this region, the whale shark is known as “Gurano Bintang” meaning “starry shark,” based on its unique colour pattern which resembles the Milky Way. Whilst locals used to fear them, they have come to believe that these animals embody the spirit of their ancestors and are a good omen, bringing luck to the fishermen and their operations. For Seven Worlds Director Lucy Wells, witnessing this incredible scene at Cenderawasih Bay was far beyond anything she could have imagined;

“Seeing a whale shark in the wild is a privilege. Usually elusive and deep sea dwelling, nothing could have prepared me for their huge, gentle beauty. I’d never seen one before, and so I was in for quite a treat. On the first day, when we visited the bagan, I saw 2 from the boat and was just absolutely thrilled. I then got the chance to get in the water, and within seconds realised that the 2 we saw were the tip of the iceberg, we were surrounded by at least 10 of these beauties. And not only that, suddenly I was able to see just how big they were! It was one of the greatest wildlife encounters of my life, and one I’ll never forget. I found that having to do my job and direct was tricky as I just could have watched them all day instead!”

Director Lucy Wells watches whale sharks gather at the surface of an Indonesian fishing platform

They didn’t speak English, and I didn’t speak Indonesian, however, our mutual joy of the whale sharks bonded us immediately.Seven Worlds Director, Lucy Wells

But for Lucy, it was not just the spectacle of seeing so many whale sharks that made the shoot so memorable;

“One of the great pleasures of my job for me is all of the people I get to meet - scientists, fixers and locals, everyone has a different story to tell. On this shoot, I got to spend a week with a group of lovely Indonesian fishermen who lived on the bagan. They didn’t speak English, and I didn’t speak Indonesian, however, our mutual joy of the whale sharks bonded us immediately. Just like the whale sharks, they were gentle and shy, but had a really cheeky side and found me hugely entertaining as I learned to say ‘thank you darlings’ in Indonesian.”

An Indonesian fisherman throws handfuls of baitfish to a pair of expectant whale sharks

CI’s whale shark satellite tagging program has provided a wealth of insights into the secret lives of the world’s largest fishVice President of Asia-Pacific marine programs at Conservation International Mark Erdmann

The remarkable relationship between these fishermen and the whale sharks at Cenderawasih Bay does not just benefit the whale sharks by way of a tasty treat. Their unusual aggregation behaviour around the bagans year round is facilitating an ongoing conservation project led by Conservation International, in which for the very first time, scientists have been able to get close enough to whale sharks to insert radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags under their skin. This innovative tagging technique is allowing researchers to build on our little knowledge of these mysterious creatures, with data guiding conservation planning such as where to set up Marine Protected Areas. Alongside this, the information collected is helping to monitor the impacts of ecotourism on whale sharks in this area, an industry that generated almost US$ 2.6 billion alone in Cenderawasih Bay National Park in 2017. If managed sustainably, this tourism can provide an alternative means of income for locals previously reliant on fishing.

“CI’s whale shark satellite tagging program has provided a wealth of insights into the secret lives of the world’s largest fish, and we are now using this information to improve the management of whale shark tourism in the Bird’s Head region. Importantly, the satellite tracks we’ve recorded have also highlighted several regions of West Papua that are frequented by migrating whale sharks that are now being considered for development of additional marine parks.”

- Vice President of Asia-Pacific marine programs at Conservation International Mark Erdmann

The Seven World’s team film whale sharks aggregating at a bagan in Cenderawasih Bay. Due to their popularity, whale sharks are facilitating a booming tourism industry which can provide a sustainable income for local people

Conservation projects like Cenderawasih Bay are providing an all-important lifeline for the endangered whale shark, whose global population has declined by more than half in the last century. In 2002 an international ban on trade in whale shark followed by legal protection of the species in Indonesian waters a decade later, showed that world leaders are too beginning to recognise the importance of protecting these unique animals. In 2013 the Raja Ampat government went one step further in declaring its entire four million hectares of water a sanctuary for all sharks.

Whilst there is a long way to go to ensure a bright future for the whale shark, such developments provide hope for a peaceful co-existence with humans, a relationship that has long existed at Cenderawasih Bay. The remarkable association between the fishermen and the whale sharks here continues to offer a powerful example of a community that has found a way to live alongside these charismatic creatures- a sight which has left director Lucy inspired long after her departure from West Papua;

“In my opinion, if local people are interested in protecting their wildlife, then we are halfway there. They care deeply for the whale sharks, and by feeding them scraps, they help to not just conserve them, but set a precedent for saving their unique and precious environment of Cenderawasih Bay as a whole… It is a lesson for all of us.”

Saving Seven Worlds

-

![]()

The last rhinos

Watch the video

-

![]()

Colliding worlds

Watch the video

-

![]()

A lifeline for the Iberian lynx

Read the article

-

![]()

Rainforest invaders

Watch the video

-

![]()

Australia's hidden past

Watch the video

-

![]()

Protecting a South American wonder of the world

Read the article

-

![]()

The vanishing forest

Watch the video

-

![]()

How you can save Asia’s jungles

Read the article

-

![]()

A sanctuary for the endangered whale shark

Read the article

-

![]()

First steps to safety

Watch the video

-

![]()

A frozen continent in a warming world

Read the article

-

![]()

The grey headed albatross faces extinction

Watch the video

-

![]()

The fisherman's good luck omen

Watch the video

-

![]()

Fur seals pups have the base surrounded

Watch the video

-

![]()

The Southern Ocean is a globally important carbon sink

Watch the video

-

![]()

An alien invader is colonising Antarctic waters

Watch the video

On location

-

![]()

The crew's most memorable filming moments

Read the article

-

![]()

The quest to film the elusive brown hyena

Watch the video

-

![]()

A fish tale with a twist

Read the article

-

![]()

Tales from Tennessee

Red the article

-

![]()

Firefly fireworks

Read the article

-

![]()

Filming in Frozen Swamps

Read the article

-

![]()

The roadie experience

Read the article

-

![]()

Drama in the troop

Read the article

-

![]()

Flying underground

Watch the video

-

![]()

Filming dragons

Read the article

-

![]()

Devils on the edge

Watch the video

-

![]()

How drones helped reveal the wonders of Seven Worlds

Read the article

-

![]()

A Peek-a-Boo veteran in the jungles of Australia

Read the article

-

![]()

Finding and filming wildlife in the jungle

Read the article

-

![]()

Walking with cats

Read the article

-

![]()

A bear called Paddington

Watch the video

-

![]()

Hiding in plain sight

Watch the video

-

![]()

Walrus on the edge

Read the article

-

![]()

Bears in the Valley of the Geysers

Read the article

-

![]()

The search for the fin whale

Watch the video

-

![]()

Gentle giants

Watch the video

-

![]()

Extreme parenting

Watch the video