Finding and filming wildlife in the jungle

By Maddie Close, Director on Seven Worlds, One Planet

Poison dart frogs

While filming for the South America episode of ±«Óãtv’s Seven Worlds, One Planet, we stayed in a village about 2hrs from Tarapoto, in the San Martín District of Peru.

But at only the size of a thumbnail, it was like finding a needle in a haystack

Each morning just before sunrise, we’d drive out, down a dirt track, to a small patch of forest and begin the hike into our location with all our camera gear. It would often take multiple trips of around 30mins each way to get all the gear in a position where we were ready to film.

The tiny frogs we were hoping to film are very site-specific and thanks to local help, we knew the rough location of a small population of the particular morph we were after. But at only the size of a thumbnail, it was like finding a needle in a haystack and we never would have found them without the keen eyes of our local team.

After rain, it became a little easier, as the males would begin to call, helping us hone down an individual’s location. At first the jungle just seemed a big tangled mess, but once at the frogs level, you could start picking out the miniature highways, that they would use to get through the forest.

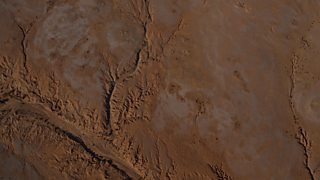

Though useful for finding frogs, the rain bought its own issues. When it rains in the jungle, it really rains.

When it rains in the jungle, it really rains.

And it just so happened that the location where we had the best chance of filming the frogs, was in a dried out river bed. Safe to say, it didn’t stay that way very long!

One day, during a particularly heavy down pour, we were debating waiting it out but the rain just kept coming, and the river was filling up, and rapidly. We had to race all the gear back down to the car, through the pouring rain. To say we looked like drowned rats was an understatement!

Cotton-top tamarins

Though significantly bigger than the frogs, no easier to film were the cotton-top tamarins that we set out to find in the dry tropical forests of Colombia.

As one of the smallest primates in the world they were not easy to spot in the tall trees

This time we had the help of satellite tracking, which would get us within the vicinity of one of the family groups pretty swiftly each morning. Once we’d tracked them, we would then sit and wait, listening out for any sound or looking for any sign of movement.

One of the group would either reveal themselves as they came to check us out or, more likely, we would hear their alarm calls. As one of the smallest primates in the world they were not easy to spot in the tall trees and are vulnerable to many predators. Families are extremely close-knit and individuals warn each other of danger through alarm calls. They have a sophisticated language of around 38 distinct sounds, which can be used to communicate specifics about a potential predator.

We’d follow them all day, every day but like many animals they slept a lot & we’d have only a few hours a day when they would be active. On top of that, the vegetation was really thick so it was super hard to see them & even harder to track with them when on the move. We would follow them as long as possible, before losing them again.

They were very unpredictable and each day would bring a different challenge.

While they could quickly run & jump through the trees, we would have to find ways around inaccessible areas and through the knotted forest. All the while trying to keep as quiet as possible so not to disturb the monkeys and even more so, the wasps! I’m pretty good with wasps at home in the UK, they’re peaceful things really, as long as you don’t aggravate them by flailing your hands around. Here, however, speaking in even a whisper as you passed their hive would cause a mass attack, as they chased you through the forest. We began to learn the locations of some of the major hives and would all quickly shift in to silence as we would creep past, hoping not to disturb them and be attacked again.

Each evening the tamarins would move off toward one of their sleeping trees and we would head out of the forest, not knowing where we would find them in the morning. They were very unpredictable and each day would bring a different challenge. We’d often sit and wait for an entire day with nothing much happening but you always had to stay attentive, just in case something super interesting happened. One day I couldn’t believe our luck. We had wanted to tell a story of their shrinking forest and on our morning commute into the forest, along the edge of the farmland, I noticed a cotton-top in the tree ahead of us.

This was the furthest out that we had ever seen them before & further out of the forest than any of the known families would usually be. Between the cotton-top and the next closet tree was nothing but a fence line so we decided to wait it out. We sat there for hours, in what felt like a game of patience. Who would give first? As we waited, we realised there wasn’t just one in the tree but a whole family. They seemed to be pretty set in staying there but we knew they would have to move on eventually and would need to use the fence line to get back toward the forest. Finally, one individual moved down the branches and started checking out the options before bouncing along the posts, freaking himself out and heading back the way he had come. It was the shots we needed to visually tell the story.

The future for cotton-top tamarins is worrying. They are listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List and are one of the rarest primates in the world. According to conservationists, their numbers have dropped across their original range, due to the pet trade & because they have lost a huge amount of their original habitat to . Estimates suggest there are as few as 2,000 adults left in the wild but thanks to the dedicated work of Proyecto Tití these intelligent, new world monkeys are holding on in a few small forest fragments.

As human populations continue to grow, the Cotton-Top Tamarins territories are being squeezed further. Proyecto Tití is leading the way in Colombia, working with local people to promote coexistence between local communities and the wildlife that they share the land with. The ongoing struggle for space is a complex problem, and one that affects not only Titis, but almost all wildlife in forests across the world.

Proyecto Tità are giving hope to these incredible animals.

There are no easy solutions because both the animals and people need space but by preventing any more loss of habitat, replanting forest, engaging local communities to become wildlife guardians and offering education, Proyecto Tití are giving hope to these incredible animals. Where these practices are already in place, Cotton-Top Tamarins are in with a fighting chance and hopefully one day will return to places where they previously thrived.

Poison dart frog: Piggyback ride

A father poison dart frog needs to relocate his tadpole.

On location

-

![]()

The crew's most memorable filming moments

Read the article

-

![]()

The quest to film the elusive brown hyena

Watch the video

-

![]()

A fish tale with a twist

Read the article

-

![]()

Tales from Tennessee

Red the article

-

![]()

Firefly fireworks

Read the article

-

![]()

Filming in Frozen Swamps

Read the article

-

![]()

The roadie experience

Read the article

-

![]()

Drama in the troop

Read the article

-

![]()

Flying underground

Watch the video

-

![]()

Filming dragons

Read the article

-

![]()

Devils on the edge

Watch the video

-

![]()

How drones helped reveal the wonders of Seven Worlds

Read the article

-

![]()

A Peek-a-Boo veteran in the jungles of Australia

Read the article

-

![]()

Finding and filming wildlife in the jungle

Read the article

-

![]()

Walking with cats

Read the article

-

![]()

A bear called Paddington

Watch the video

-

![]()

Hiding in plain sight

Watch the video

-

![]()

Walrus on the edge

Read the article

-

![]()

Bears in the Valley of the Geysers

Read the article

-

![]()

The search for the fin whale

Watch the video

-

![]()

Gentle giants

Watch the video

-

![]()

Extreme parenting

Watch the video

Saving Seven Worlds

-

![]()

The last rhinos

Watch the video

-

![]()

Colliding worlds

Watch the video

-

![]()

A lifeline for the Iberian lynx

Read the article

-

![]()

Rainforest invaders

Watch the video

-

![]()

Australia's hidden past

Watch the video

-

![]()

Protecting a South American wonder of the world

Read the article

-

![]()

The vanishing forest

Watch the video

-

![]()

How you can save Asia’s jungles

Read the article

-

![]()

A sanctuary for the endangered whale shark

Read the article

-

![]()

First steps to safety

Watch the video

-

![]()

A frozen continent in a warming world

Read the article

-

![]()

The grey headed albatross faces extinction

Watch the video

-

![]()

The fisherman's good luck omen

Watch the video

-

![]()

Fur seals pups have the base surrounded

Watch the video

-

![]()

The Southern Ocean is a globally important carbon sink

Watch the video

-

![]()

An alien invader is colonising Antarctic waters

Watch the video