Freedom rides and civil rights marches

Freedom rides

As with eating areas and schools, there was resistance to desegregationRemoval of laws that separate people from different races in public places and day-to-day life. buses and bus stations. In May 1961, the COREAn American civil rights group founded in 1942 known for its use of non-violent protest. organised âfreedom ridesâ. On these rides, black Americans deliberately broke segregationThis meant that white people and black people had to live separately. The areas of society affected by segregation included churches, hospitals, theatres and schools. customs and laws. This was to highlight that despite the US Supreme CourtThe ultimate court of appeal in the USA. It makes the final decision on whether a law is permitted by the US Constitution. ruling that segregation on buses was unconstitutional, there had been little change across the South.

The first freedom ride was on 4 May 1961 and it went from Washington, DC, to New Orleans. It travelled through many of the southern states.

- In Anniston, Alabama, one bus had its windows smashed and a petrol bomb thrown into it, but the passengers escaped unharmed.

- When the next bus reached Anniston, the passengers were taken off the bus and attacked by an angry mob of white Americans.

- Freedom RidersCivil rights activists who travelled on public transport between states to show desegregation had not been achieved. were also attacked in Birmingham and Montgomery, in Alabama. Others were arrested in Jackson, Mississippi.

The police did little to help the Freedom Riders, so President John F Kennedy sent US MarshalsOfficers in the USA who enforce federal laws and respond to crisis situations. to protect them. In September 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission ordered that buses and bus stations must be desegregated immediately.

Birmingham march, 1963

By the spring of 1963, Birmingham, Alabama, became the focus of civil rights protests. This was because the authorities had done nothing to desegregate public facilities and nearly half the population were black Americans. Birmingham had no black police officers, firefighters, bus drivers or store cashiers. Only 10 per cent of the cityâs black population was registered to vote. The civil rights leaders in Birmingham realised that there were two factors that could help them to get publicity for their protests:

- The local commissioner for public safety, Eugene âBullâ Connor, held racist views.

- Birmingham had a lot of members of the Ku Klux KlanA white supremacist organisation that used violence and intimidation to target black, immigrant, Jewish and Catholic people. Its members believe, based on incorrect and unscientific ideas about evolution, that white people are superior and should therefore hold the power in society. If these people reacted violently to the protesters, it would generate a lot of media coverage that was sympathetic to the civil rights cause.

The first civil rights march, in April 1963, ended with Dr Martin Luther King Jnr and other leaders of the march being arrested and put in prison. While in prison, King wrote âLetter from Birmingham Jailâ, which explained the case for continuing to protest and for an end to discriminationTo treat someone differently or unfairly because they belong to a particular group.

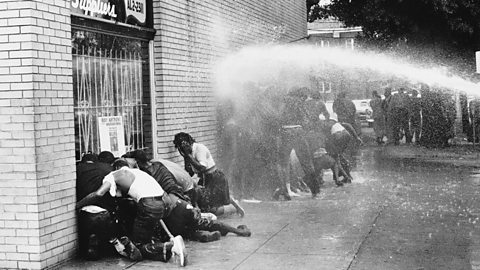

At the beginning of May, a second set of marches began. Many of the marchers were young people, mostly teenagers, but some were as young as six years old. The marches were known as the âchildrenâs crusadeâ. The police arrested so many protesters that the prisons were full, and they used police dogs and water cannons to force the protesters off the streets. This was seen on television and in photographs around the world. It created a lot of sympathy for the protesters.

President Kennedy sent a representative to negotiate an end to the protests. George Wallace (the governorA person who is elected to lead a stateâs government in the USA. of Alabama) and the Ku Klux Klan tried to stop this, but the white Americans who owned businesses wanted the protests to end. Birmingham began to desegregate, and the protests ended. Kennedy was now convinced that America needed a Civil Rights Act to give African Americans equality and to make sure these protests did not happen again.

March on Washington, 1963

In August 1963, CongressThe legislative body of the US government, made up of the Senate and the House of Representatives. was debating President Kennedyâs civil rights billA proposed new law. When a bill is approved by Congress and the president, it becomes an act and is now the law. Many of the civil rights organisations - including the NAACPThe National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was created in 1909 to eliminate race-based discrimination across the United States of America. COREAn American civil rights group founded in 1942 known for its use of non-violent protest. the SNCCStudent Nonviolent Coordinating Committee initially promoted non-violent protest. and the SCLCSouthern Christian Leadership Conference. A civil rights organisation set up in 1957 based on Christian values that peacefully campaigned against segregation in the USA. - organised a joint march in Washington, DC, to show their support for the bill. Some worried that this would lead to violent clashes with protesters. Kennedy asked for the march to be called off in case it damaged the chances of the bill being passed.

The Lincoln Memorial commemorates the life of Abraham Lincoln, the president who introduced the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. In front of it, around 250,000 people gathered to hear speeches and music about the need to improve civil rights. It is estimated that between 20 and 25 per cent of the people marching were white. The final speech of the day was by King. In this complex speech, known as âI Have a Dreamâ, he explained how he hoped that black and white Americans could live together as equals, linking his beliefs to the American dream and the US Constitution.

Despite the profile of women in the Civil rights movementAn organised set of activities that brought about a change in the treatment of people from different races in American society. like Rosa Parks and Ella Baker, women were given limited roles. For example, they sang or introduced male speakers at the event. Prominent women were instructed to walk in a group behind the male leaders, meaning Kingâs wife, Coretta Scott King, couldnât walk beside her husband. The limited role of women at this event highlighted the inequalities in both race and gender in America.

The March on Washington further raised the profile of the civil rights movement and increased awareness if the effectiveness of peaceful protest. However, there was still a lot of resistance to equality in Congress, and violence against black Americans continued. President Kennedy was assassinateMurder for religious or political reasons. in November 1963, but his successor, Lyndon B Johnson, managed to get Kennedyâs civil rights law passed in 1964.

More guides on this topic

- Anti-Communism c.1945-1954 - OCR A

- African Americans c.1945-1954 - OCR A

- Broadening of the campaigns for civil rights - Race - OCR A

- Broadening of the campaigns for civil rights - Women's rights - OCR A

- Broadening of the campaigns for civil rights - Gay rights - OCR A

- Politics and protest - OCR A

- Social problems and attempts to tackle them - OCR A