The later 19th century

Edwin Chadwick

In the 1840s attitudes began to change. Edwin Chadwick was a civil servant employed by the Poor Law CommissionThe body set up by government to supervise the help given to the poor out of local taxes called rates.. He was asked by parliament to investigate living conditions in Britain.

His 1842 Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population concluded that much poverty and ill-health was caused by the terrible living conditions and not by idleness. It shocked public opinion.

Statistics in the report showed just how unhealthy industrial towns and cities were, even for the wealthier inhabitants.

Chadwick concluded that three main things were needed to improve health:

- refuse removal

- an effective sewage system and clean running water in every house

- a qualified medical officer appointed in each area

For a few years little happened. Chadwickâs report was strongly opposed by many MPs who were nicknamed the Dirty Party. Chadwickâs recommendations meant that councils would have to increase the rates A payment made by householders to their local council. and this would be unpopular with the better-off citizens. It was the cholera epidemic of 1848 which led to a change of mind by Government.

In the outbreak of 1848/49, over 3,000 people died in the county of Glamorgan. There were at least 350 deaths in Cardiff and 1,389 in Merthyr Tydfil from cholera.

The 1848 Public Health Act set up the Board of Health - the first time that Government had legislated on health issues. Local authorities were given the power to appoint an officer of health, who had to be a legally qualified medical practitioner, and to improve sanitation in their area, eg collect rubbish, build sewers and provide a clean water supply.

Dr John Snow

In 1854, cholera struck again. In London, Dr John Snow studied the spread of cholera in the Broad Street area. He noticed that the victims had all drank water from the pump in the street. He persuaded local officials to stop people using the pump and the number of cases fell rapidly.

By observation Snow had shown the link between bad water and cholera â the Broad Street water had been pumped from the Thames. If people had clean water then disease would be reduced.

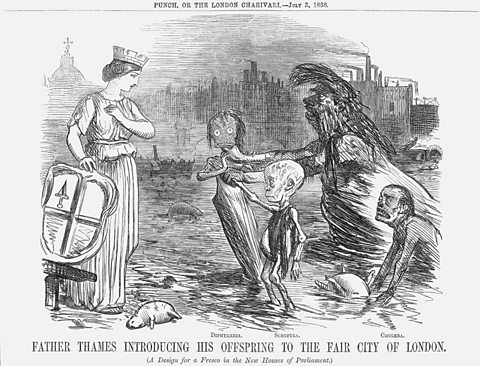

In 1858, London was affected by the Great StinkA period of hot weather that exacerbated the smell of raw sewage and industrial pollution in the River Thames. . Soon after, work began on the London sewage system. By the time it was completed 13,000 miles of pipes had been laid, under the direction of Joseph Bazalgette, the chief engineer. However, relatively few councils followed Londonâs example. By 1872, only 50 councils had Medical Officers of Health. The huge cost of carrying out improvements was the biggest obstacle.

Health boards in Wales 1848â1875

Between 1848 and 1875, 17 towns in south Wales petitioned to form Boards of Health, including Cardiff, Swansea, Merthyr Tydfil, Aberdare and Maesteg. The effectiveness of the local Health Boards varied greatly as they had limited powers and relied heavily on local interest and goodwill.

In Merthyr Tydfil, a public water supply was established and a reservoir was completed in 1863, and sewage pipes were laid underground.

In Cardiff, nearly ÂŁ100,000 was invested in drainage and water supplies between 1848 and 1872.

The reports of the new Medical Officers of Health (MOHs) also provided useful evidence and statistics on conditions and death rates. For example, in 1858, the MOH for Cardiff provided a list of 222 dwellings housing 2,920 people, including one house with 26 inhabitants. These figures supported the need for improvements.

1875 Public Health Act

Pressure began to mount on Government. Finally the Public Health Act of 1875, forced councils to carry out improvements.

These included the provision of clean water, proper drainage and sewage systems and the appointment of a Medical Officer of Health in every area.

During the 1870s, in fact, a series of new laws led to improvements in public health and hygiene.

| Year | Act |

| 1875 | Artisans Dwellings Act allowed councils to clear slums and build better homes for working families. |

| 1876 | Sale of Food and Drugs Act banned the use of harmful substances in food, eg chalk in flour. |

| 1876 | Laws against pollution of rivers were introduced. |

| 1878 | Epping Forest in London became a protected open space for local people to enjoy. |

| Year | 1875 |

|---|---|

| Act | Artisans Dwellings Act allowed councils to clear slums and build better homes for working families. |

| Year | 1876 |

|---|---|

| Act | Sale of Food and Drugs Act banned the use of harmful substances in food, eg chalk in flour. |

| Year | 1876 |

|---|---|

| Act | Laws against pollution of rivers were introduced. |

| Year | 1878 |

|---|---|

| Act | Epping Forest in London became a protected open space for local people to enjoy. |

By 1884 most working men were given the vote. From this point on their demands were more likely to be heard by the MPs who wanted their votes.

1870 Education Act

The 1870 Education Act made schooling compulsory. Some schools taught health education, while improved literacy enabled the public to read government pamphlets, eg about health, diet etc. Building regulations improved the quality of working class housing.

By the late 19th century the industrial revolution was finally bringing benefits to the working class. Laws had been passed limiting hours of work and improving working conditions.

Higher wages helped people get better houses and a healthier, more varied diet. Industrialisation brought cheaper, mass-produced products, eg soap, disinfectant, toilets, cotton clothing etc, which improved health.

Mixed progress

Even after the passing of the Public Health Act of 1875, progress was not as rapid as had been hoped. While some councils, like Birmingham, made rapid progress in building sewers and water supplies etc, others lagged behind.

This description of the River Rhondda, written by Dr Bruce Low, Medical Officer of Health, in his annual report in 1893 illustrates the fact that in some of the poorer areas of the country progress was slow.

The river contains a large proportion of human excrement, stable and pigsty manure, congealed blood, offal and entrails from the slaughterhouses, the rotten carcasses of animals, cats and dogs... old cast-off articles of clothing and bedding, and boots, bottles, ashes, street refuse and a host of other articles... In dry weather the stench becomes unbearable.

The late 19th century had seen great strides in public health provision and hygiene. However there was still a lot of ill-health. In 1900, life expectancy was still below 50 and 165 infants out of every 1,000 still died before their first birthday.