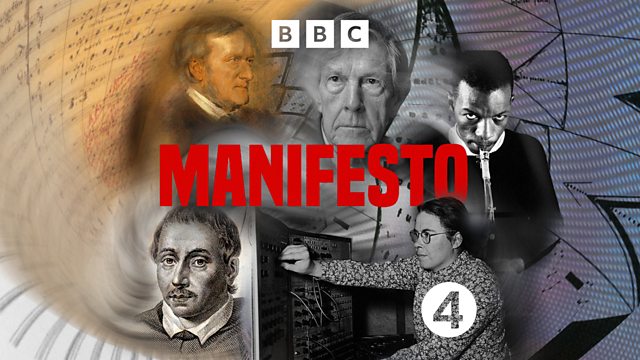

Music Manifestos

Music has always been more than entertainment or something beautiful to the ear. Exploring the radical worlds where music and politics meet, in classical, jazz, electronic and pop.

Music has always been more than entertainment or something beautiful to the ear. It has a political life too, an art form capable of changing the world as well as enchanting it. Just as political activists and thinkers wrote manifestos in the modern era, so did artists and musicians. The music manifesto is where music, art and politics meet, sometimes pushing music to its limits - and beyond.

The early 20th century saw an explosion of artists’ manifestos linked to the great avant-garde movements like Futurism, Surrealism and Dada. Music followed suit. Luigi Russolo wrote The Art Of Noise (1913), a Futurist music manifesto, making the case for vast, industrial soundscapes and the noise of the metropolis becoming the music of the modern era: ‘…a revolution of music paralleled by the increasing proliferation of machinery...air and gas inside metallic pipes, the rumblings of engines breathing with animal spirits, the rising and falling of pistons, the roar of railway stations and foundries, power plants and subways!’

Music manifestos pushed the boundaries of what music could – and should – be, drawing it away from established ideas of melody, pitch, harmony and tone and incorporating non-orchestral sound and mechanical and electronic instruments. Above all, music manifestos insisted music should be a force of change in our social and political life, not a rarefied art floating above it.

The Fluxus manifesto for music emerged from the art movements of the 1960s, building on the work of American composer John Cage, whose own manifesto, The Future of Music: Credo (1937), pioneered the use of electronic instruments. British composer Cornelius Cardew’s manifesto for Scratch Music (1969) tapped into the counter-culture, radicalising the idea of the orchestra itself. These were fully improvised public performances, making the orchestra a place of inclusion for musicians and non-musicians alike. In the US, jazz sax player Ornette Coleman announced The Shape of Jazz to Come – and wrote a manifesto for a new musical system he named ‘Harmolodics’ (‘the players express their opinions free of the leader…in harmolodics the melody is not the lead’) democratising jazz.

There have been modern music manifestos too. In pop music, ZTT records were inspired by the Futurists and signed The Art of Noise, named after Russolo’s 1913 music manifesto. Pauline Oliveros’ manifesto for Quantum Listening (1999) revolutionises how we listen to music and the world surrounding us. More recently, musicologist Daniel Chua’s manifesto, ‘An Intergalactic Music Theory of Everything’ (2021), launches the music manifesto into outer space - music must be at the centre of future communications with extra-terrestrial life.

Hearing from musicians, critics and writers across classical music, jazz, electronic and pop, this feature explores the music manifesto as a political as well as artistic intervention - in turns explosive, brave and unhinged - and in each case, a push for freedom, a musical call-to arms. How do the radical visions of tomorrow ignite our music today?

Contributors include: music writer Paul Morley, New Yorker critic and author Alex Ross, singer and broadcaster Catherine Bott, electronic musicologist Adam Harper, jazz critic and author Kevin Le Gendre, composer Howard Skempton, Director for the Centre of Deep Listening Stephanie Loveless and astro-musicologist Daniel Chua.

Readings by Elliot Levy and Candace Allen

Produced by Simon Hollis

A Brook Lapping production for ±«Óãtv Radio 4

Last on

Broadcasts

- Tue 20 Feb 2024 11:30±«Óãtv Radio 4

- Sat 23 Mar 2024 23:30±«Óãtv Radio 4