Eight things you might not know about Notting Hill Carnival

Caribbean carnival has come a long way, from the burnt canes and heavy chains of 18th Century processions to the bikinis and sequins of today. In the latest You’re Dead To Me podcast, Greg Jenner is joined by historian Prof Meleisa Ono-George and comedian Nathan Caton to discuss the history of Notting Hill Carnival.

Here are some of the unexpected things they uncover…

-

![]()

You're Dead To Me podcast: Notting Hill Carnival

Greg Jenner goes back to 18th century Trinidad to learn the roots of the Notting Hill Carnival.

1. Caribbean carnival has its roots in a blend of African, European, and Trinidadian traditions.

In 1783 when planters in the formerly French colonies of Martinique, Grenada, and Dominica responded to an edict by the Spanish king, they moved themselves and their slaves to Trinidad, bringing with them the French tradition of raucous carnival and fancy masked balls.

Notably, while the enslaved people were confined to their quarters, their owners dressed up to mock them during a masque known as negre jardin. They blacked-up their faces, carried chains, and recreated the ritual of canboulay (forcing the enslaved people to harvest the sugar cane when the fields were on fire), by burning canes, singing, dancing, and chanting. So, shockingly, Carnival began as white people mocking black people.

2. Carnival costumes looked very different to those of today

Slavery was abolished in the Caribbean in 1838, and the liberated people now fully embraced carnival as their own. Their Mas costumes were often based upon West African myths and were mostly scary rather than sexy.

Surviving depictions show black revellers wearing whiteface and devil masks, or dressing as bats, skeletons, and midnight robbers. It was common for revellers to douse spectators with animal bladders filled with water. And, to the immense shock of the authorities, men and women dressed up as the opposite gender, wearing fake genitals or menstrual blood and doing provocative sexualised dances. It was quite the sight, and very noisy!

3. Revellers have historically used anything to make music from sticks and gin bottles to oil drums

The Caribbean is famed for its rich musical heritage, from calypso to reggae, but it wasn’t always so easy to play at carnival. After emancipation in 1838, authorities in Trinidad and Tobago tried to suppress carnival’s dangerous energy, and between the 1860s and 1890s banned the lighted torches, drums, and stick-fighting traditions that the people loved so much. Riots ensued.

This was the origin of the steel bands that, after WW2, then made great use of the empty oil drums left behind by the military

But the new rules stuck, so Trinidadian people had to get creative. So-called tambou-bamboo bands instead invented a range of improvised tuned percussion instruments: bamboo tubes of varying lengths, gin bottles "played" with spoons, metal scrapers, and later biscuit tins, hubcaps, and brake blocks. This was the origin of the steel bands that, after WW2, then made great use of the empty oil drums left behind by the military.

4. One of the first British Caribbean carnivals was held indoors, in January

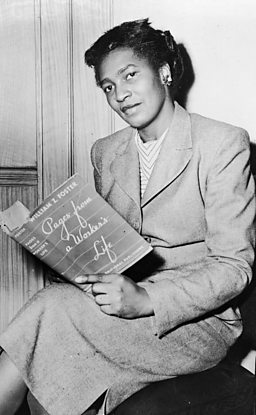

An early Caribbean carnival event was held on January 30th 1959, in the chilly setting of St. Pancras town hall, in London. It was hosted by the black political activist and journalist, Claudia Jones.

Born in Trinidad and raised in America, Claudia Jones had been jailed and then deported from New York in 1955. Her crime was being a communist. But she set about making the most of her time in Britain. She founded one of the first the black British newspapers, The West Indian Gazette, led anti-fascist marches upon Whitehall, and decided to hold an annual London Caribbean Carnival event, complete with a painted palm tree backdrop, indoor dancing to calypso singers, and plenty of rum. She’s now known as the Mother of Notting Hill Carnival.

5. Carnival in Britain was inspired by a series of racist attacks

In late August of 1958, race riots had broken out in both Nottingham and the Notting Hill area of west London. Mobs of mainly white youths attacked black people and their houses, causing great damage and harm. Then in 1959 Oswald Mosley stood as the Fascist Union Movement candidate for North Kensington, whipping up yet more racist hatred. Around the same time, a black man named Kelso Cochrane was fatally stabbed in Kensal while walking home from work.

This prolonged campaign of racial violence deeply affected the black British population and inspired various forms of cultural resistance, including an early form of carnival. One of Claudia Jones’ writers for the West Indian Gazette, Donald Hinds, remembers that Jones sought to “wash the taste of Notting Hill out of our mouths” following the riots. The event ran annually until her early death in 1964.

6. The idea for an early Notting Hill street Carnival came to a local social worker, Rhaune Laslett, in a dream

Rhaune Laslett, who was of Native American descent, described the idea coming to her in a kind of vision quest known as a Hamblecha. She had been dealing with a landlord/tenant dispute when: ‘Suddenly I had this sort of vision that we should take to the streets in song and dance, to ventilate all the pent-up frustrations born out the slum conditions.’

Her original event, Notting Hill Fayre, was not so much a Caribbean carnival as a multicultural street party. As she put it: ‘We felt that although West Indians, Africans, Irish and other nationalities all live in a very congested area, the very little communication between us…’ The 1965 Fayre therefore included pageants, procession, musicals; international song and dance; Dickens and drama recitals; Jazz and folk music; poetry and choir night; a torchlight procession; and fireworks. As more local Caribbean performers became involved, the event grew into a bigger jump-up every year.

7. To this day Notting Hill Carnival enlists 40,000 volunteers

Claudia Jones and Rhaune Laslett have both been described as the driving forces behind Notting Hill Carnival. Another key figure was Leslie ‘Teacher’ Palmer who gave it a boost in 1973 when he introduced the static sound systems, electric generators, costumed parades, steel drum processions, and extended the procession route. Crucially, he also expanded it from a Trinidadian celebration to encompass all islanders, making it a shared festival for London’s Caribbean community. By 1975, the carnival had tens of thousands of people in attendance. This has often been described as the first modern Notting Hill Carnival.

But, despite the obvious importance of Jones, Laslett, and Palmer, Carnival has always been a shared community project, and drummers, dancers, singers, teachers, costume makers, and organisers all continue to play a vital part. A whopping 40,000 people volunteer every year to make Carnival what it is.

8. Carnival has nearly been ended multiple times, but it keeps coming back

So, carnival 2020 might be cancelled due to COVID, but it won’t be the first time it has faced setbacks. It was curtailed in the 1890s in Trinidad, and the 1964 carnival in London was temporarily paused after the death of Claudia Jones.

In 1976, police harassment of the Notting Hill Carnival led to mass riots and subsequent calls for the cancellation of the event. And following the 2011 London Riots, carnival only went ahead with a 7pm curfew. But it’s always found a way to bounce back, and it’s safe to say that Notting Hill Carnival, with its million-strong community of dancing attendees, will be back with a bang, as soon as it’s safe.

More from Radio 4...

-

![]()

You're Dead To Me

Greg Jenner brings together the best names in comedy and history to learn and laugh about the past.

-

![]()

Seriously...

A rich selection of documentaries aimed at relentlessly curious minds.

-

![]()

How They Made Us Doubt Everything

How some of the world's most powerful interests made us doubt the connection between smoking and cancer, and then how the same tactics were used to make us doubt climate change.

-

![]()

Scientifically...

The home of the best science programmes from ±«Óãtv Radio 4 introduced by Dr. Alex Lathbridge.