The Big Craving-Beating Experiment

You probably know the feeling – whether it’s crisps, chocolate, coffee or something like nicotine or alcohol: you start thinking about it, and wanting it, even though you don’t want to. The more you think about it, the worse the craving gets. So what’s the answer?

A counterintuitive answer has been put forward by Dr Carey Morewedge of Boston University – that instead of trying to stop ourselves thinking about things we want to quit, we should use our imagination more, in a very specific way.

His theory is that by imagining eating the food we want 30 times over, then we will reduce our craving for it.

If his theory works, this could be a simple trick we could all use to help us conquer our bad habits – so we decided to put it to the test.

The experiment

We invited chocolate-loving volunteers to take part in several experiments based around Carey’s ideas. None of them were told what the experiment was, only that it involved tasting chocolate.

- In the first experiment, volunteers were placed individually into separate booths so that they wouldn’t be influenced by anyone else around them. They were told they were tasting a new type of chocolate and were given a plate of 30 chocolate sweets. But half of the volunteers were asked, before tasting the chocolates, to try to imagine eating 3 of them; and the other half of the volunteers were asked to imagine eating 30 of them. They were then told they could taste as many of the chocolates on the plate as they wanted, and we recorded how many each person ate to look for differences between those who had imagined eating 3 and those who had imagined eating 30.

- In the second experiment, Carey took two groups of volunteers into rooms and asked one group to imagine eating 3 chocolates and the other, 30 chocolates. They were then asked to fill in a questionnaire as a distraction, but whilst they were doing that, they were allowed to eat freely from bowls of chocolates in the room. We measured the amount of chocolate that each group ate to look for differences between the group which had imagined eating 3 and that which had imagined eating 30.

- In the third experiment, we asked volunteers to rate their cravings for chocolate, and sent them home for 2 weeks with a large bag of chocolates. We asked them, every time they had a craving to eat chocolate, to imagine eating either 30 (half the volunteers) or 3 (the other half of the volunteers). They weren’t told the aim of the experiment, and at the end of 2 weeks we asked them to rate their level of cravings for chocolate again. We then compared the change in craving levels for the two groups. This was the first time Carey’s theory had ever been tested in a more long-term and real-world scenario.

The results

- When tested individually there was no significant difference between the number of sweets eaten by people asked to imagine eating 3 and those to imagine eating 30 (11% less in those imagining 30) – this could have been for a number of reasons. Some people thought that they were supposed to eat the number that they had imagined, and some ate one of each colour and this may have confounded the results. Carey, and others, have found that generally when tested individually, those asked to imagine eating 30 eat fewer than those asked to imagine eating 3.

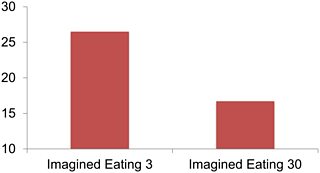

- When tested in a group, however, there was a very clear difference between the two groups in our experiment. The group asked to imagine eating 30 ate 37% less than those asked to imagine eating just 3.

- In our 2 week experiment, we also saw a significant difference between the two groups. The group asked to imagine eating 3 chocolates saw a small drop in craving levels (on a rating of 1-5 they saw an average rating drop of 0.41), whilst the group asked to imagine eating 30 chocolates each time they felt a craving saw their average craving levels drop a lot more (an average rating drop of 0.79).

How it works

When we are eating something nice, the first few mouthfuls are particularly pleasant, but it becomes less delicious the more we have. In fact the same is true of any experience we have – good or bad. It’s called ’habituation’ – our brain simply becomes less stimulated by the sensations. In order to keep enjoying something, the ideal thing to do is change it slightly. That’s why you tend to eat more of foods where there a variety of flavours available, and why – even if you think you’re full from a main course – you can often find room for pudding!

This is the key to how the ‘imagining’ trick works. By imagining eating something you can actually harness this ‘habituation’ process, and make your brain ‘bored’ of the thing that you had wanted to eat without actually eating any of it at all.

Because of this, the technique only works for the specific thing you are imagining, or at least something very like it (it has been shown to work with a whole range of different foods). So, if you want to stop yourself eating the rest of a packet of crisps, you have to imagine eating 30 of those crisps; if you want to stop yourself drinking another cup of coffee, you have to imagine yourself drinking 30 good swigs of coffee.

Hopefully this will help you break a cycle of cravings and quit a bad habit.

Interactive guide