Scientists predict that the world will be 1.5 degrees hotter by 2030. In some parts of Northern Kenya, it’s already 2 degrees hotter.

We knew we wanted to focus on maternal health for one of our short films. We’ve worked on a few climate change projects and it’s clear that it’s women who are bearing the brunt of it. In Northern Kenya, women do most of the work. They cook, feed the children, build the houses, do the housework and walk for hours in the heat to find water. Some girls are pulled out of school because they have to help their mothers with the household chores.

With longer and more frequent droughts, water points have been drying out faster, forcing women to walk for about six hours or even longer in the harsh drylands to find water. And when they do find water, it’s usually dirty or contaminated but they have no choice but to drink it. Some of the women we spoke to told us that when they find a waterpoint, there’s usually a scramble for water, and some pregnant women have even lost their babies in these scrambles. All the women we spoke to said that they had chronic back pain, swollen feet and often had nose bleeds from walking long distances in the heat to find water.

Welcomed with smiles

The women at Loima sub-county welcomed us with smiles and songs and were willing to speak to us on camera about the impact longer droughts and increased temperatures are having in their lives. When we arrived at their homestead, I stepped out of the car in my flat shoes and could not stand the heat of the ground for more than 10 minutes. I don’t know how these women do it in their thin sandals made from goat skin.

Their bodies have had to adapt to a lot. I asked Esther, the pregnant woman featured in the first film, “What have you eaten today?” She told us she had a cup of black tea in the morning. We tried to offer her food, but she would just give it to her children, who had also not had a meal that day. When she showed us where and how she fetched water, we held our breath, afraid she might injure herself and her baby. She was eight and a half months pregnant. During the long droughts, the community comes together and digs holes in the dry river bed about two to three feet deep (less than one metre) to find water.

For the mental health story, we were less sure whether Lomilio would be willing to speak to us, but he and his family welcomed us with smiles and were very open with us.

Sobering stories

But by day 2, the crew started getting very quiet, contemplating as Lomilio told us how he lost all his livestock one day during a flash flood in March 2020. He had about 900 goats. It was sobering to watch a man of around 70 years old break down in front of us because he had lost his livelihood. It was evident how much he loves his children and wants a good life for them, but he can’t provide that. He said that there is only darkness left in his heart. Luckily his friends donated some goats to him, but it hadn’t rained since that fateful day in March 2020, so his newly acquired goats were dying too.

After we listened to his story, one of my colleagues came up to me and said he was going to buy some food for them. It seems in those quiet moments we were all thinking the same. We are not supposed to pay people for an interview but when you go to these kind of places, you can’t just interview them and leave.

We chipped in and bought them enough food to last a couple of months, but we were worried that other people nearby who had seen us come to the village would take it from them. They, too, are suffering from longer droughts, with no food or water for their families. This is the reality of climate change in many parts of Africa.

Life is getting harder

We sometimes get asked why our projects focus on climate adaptation rather than mitigation. Looking at Lomilio, I thought, what can I tell him? The only way his family emits carbon is when his wife cooks food for his kids using charcoal. I couldn’t possibly tell him not to do that? Esther walks 28 kilometres to get to the clinic for her antenatal visits in almost unbearable heat. The nurse said she was due any moment and told her that if her waters broke, she was to get a motorbike to bring her to the clinic. Her friends would have to chip in to afford this motorbike ride to the clinic. I couldn’t possibly tell her not to use the motorbike to go to the clinic because it emits carbon.

Both Lomilio and Esther live day to day. They do not think in terms of carbon emissions but wake up hoping they will be able to find food and water that day. They cannot plant trees, cannot peacefully protest or recycle. They don’t own cars and have never been on a plane.

Africa contributes to 3.6% of global carbon emissions, but it is people like Lomilio and Esther who bear the brunt of the impact of climate change. They don’t know what COP26 is, they just know that life is getting harder, and weather patterns more extreme.

It is late October 2021 as I am writing this. COP26 ends on 11 November and people around the world will soon start getting ready for Christmas. I can’t help but wonder how many times Esther and Lomilio’s wife will have to walk long distances in search for water in the next two months, then again in 2022. Communities like these urgently need help. They needed help yesterday. This is what we hope leaders and policymakers watching these films can understand.

±«Óătv Media Action is working with journalists and weather and climate scientists in East Africa to help farmers, fisherman and pastoralists better understand and prepare for climate-related weather changes. Read more about our work.

Watch the series

-

Mosquitoes in the mountains, Nepal

Mosquitoes and mosquito-borne diseases like malaria used to be confined to low-lying areas of Nepal. But in the last three years, there have been over 900 cases of malaria in the mountain regions. Parbati Bhat, who has been a community health volunteer for 38 years, says treating malaria cases has now become a new part of her role. -

The flood that took everything, Kenya

The consequences of extreme and unpredictable weather conditions can take a severe toll on mental health, as well as physical health. Pastoralist Lomilio Ewoi Erot lost his livelihood when his herd of hundreds of goats was swept away in a flood; he speaks of his struggles with mental health after becoming unable to provide for his family. -

Feeling the heat, Bangladesh

Increasing temperatures, particularly in big cities like Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, have profound effects on human health. Nazma Begum, who lives in a slum in Dhaka, described the impact of working 14 hours a day in an overheated garment factory, while others suffer from skin conditions and heatstroke. -

When snow becomes rain, Nepal

Climate change is destabilising food production in many parts of the world. Angyel Jung Bista, an apple farmer in the village of Kabgeni in Nepal, struggles to grow apples as warmer weather, heavy rainfall and floods pollute the water, prevent apples from growing, and contribute to the spread of waterborne diseases. -

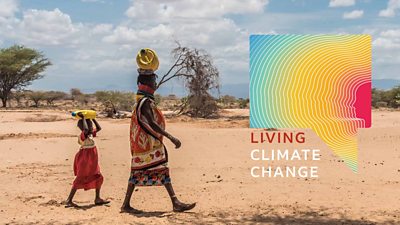

The long walk to water, Kenya

Pregnant Kenyan mother Esther Elaar walks over two hours a day to get to a water source, then carries a heavy, 20-litre jerrycan all the way home again. Prolonged droughts and changing weather patterns driven by climate change have made everyday life an increasing struggle for people in northern Kenya. Women in the region have noticed an increase in miscarriages and stillbirths which they attribute to the extreme conditions. -

Salt in the water, Bangladesh

In coastal regions in Bangladesh, increased levels of salt in fresh water are contributing to reproductive health problems and cardiovascular diseases. Shabjan Begum, who lives in a fishing village on the southern coast reliant on the saline water for food, water and fishing, knows these health risks first-hand, through her own experience and that of her family and neighbours.

Behind the scenes

-

Behind the scenes in Kenya

Our project director Diana Njeru shares her reflections on extreme heat and drought, and their impacts on health, in northern Kenya. -

Behind the scenes in Nepal

Our communications manager, Om Rai, reflects on the journeys to meet Angyel Bista and Parbati Bhat. -

Behind the scenes in Bangladesh

Film producer Polash Rosul and Head of Production Bishawjit Das share the storygathering process behind our Living Climate Change series in Bangladesh.