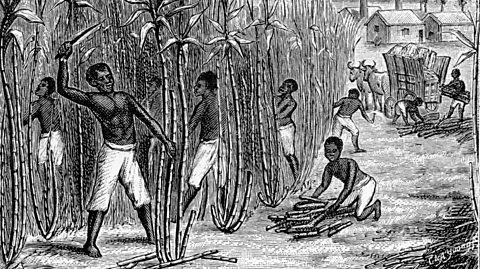

What did the trade in enslaved Africans do for British ports?

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYQuick version

British ports were heavily involved in the trade in enslaved people. As a result, these ports grew rapidly and generated great wealth for the traders who sailed from them.

Some traded directly in enslaved Africans.

- In 1771 Liverpool-based ships traded almost 30,000 enslaved Africans. The city controlled 40% of the European trade in enslaved Africans.

Other cities traded in goods that were products of the trade in enslaved Africans.

- Glasgow controlled 50% of the American tobacco trade.

- London's ports handled most of the sugar imported from plantations in the Caribbean.

- Bristol's workshops created goods that were traded for enslaved Africans.

Learn in more depth

How extensive was British trade in enslaved Africans?

The table below shows the figures for the trade in enslaved Africans through the main British ports in 1771.

| Port | Number of ships | Enslaved people |

|---|---|---|

| Liverpool | 107 | 29,250 |

| London | 58 | 8,136 |

| Bristol | 23 | 8,810 |

| Lancaster | 4 | 950 |

Glasgow also carried half of Europe's tobacco trade at this time, an industry which depended upon enslaved labour to grow the tobacco in Britain's colonies in the Americas.

How did the trade in enslaved Africans affect British ports?

The trade in enslaved people brought a great deal of wealth to the British ports that were involved.

Two hundred years ago the average working person earned ÂŁ35 a year. A single enslaved African in good condition could be sold in the Caribbean for ÂŁ25.

Many other cities also grew rich on the profits of industries which depended on materials produced by enslaved workers, such as cotton, sugar and tobacco.

Ports such as Bristol, Liverpool, and Glasgow sent out many slaver ships each year, bringing great prosperity to their owners:

1792 was the busiest trading year for Britain, when 204 ships left to carry enslaved people from Africa to the Americas â this amounted on average, to four ships a week.

From 1791 â 1807, British ships carried 52% of all enslaved people taken from Africa.

From 1791 â 1800, British ships delivered 398,719 enslaved people to the Americas.

Glasgow and the trade in enslaved Africans

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYIn total, it is thought that nearly 5,000 enslaved Africans were transported by Scottish slave ships. Slave ships sailing from Glasgowâs ports carried around 3,000 of that number.

The city was more involved in importing products with direct links to slavery, such as tobacco. It also benefited from financial donations of plantation owners such as the Glassford family, who were commemorated by having a city centre street named in their honour â Glassford Street.

By 1720, Glasgow imported over 50% of all the American tobacco grown by enslaved labour and used the profits to advance the city, earning it the title of the âSecond City of the Empireâ. (Source: The Scotsman: Lost Glasgow: The tobacco lords.)

Institutions such as the University of Glasgow received up to ÂŁ198 million (in todayâs money) in donations from individuals involved in the trade in enslaved people. (Source: ±«Óătv News.)

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYLiverpool and the trade in enslaved Africans

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYDuring the 18th century, Liverpool made about ÂŁ300,000 a year from the trade in enslaved Africans. The rest of Britain's trading ports put together made about the same amount again.

In the 1780s Liverpool-based vessels alone carried more than 300,000 Africans into slavery. By 1795, Liverpool controlled over 60% of the British and over 40% of the entire European slave trade.

Although Liverpool merchants engaged in many other trades and commodities, involvement in the trade in enslaved people occupied the whole port.

The wealth acquired by the town was substantial. The trade in enslaved Africans made a great deal of money for the city's docks. The stimulus it gave to trading and industrial development throughout the north-west of England and the Midlands was to have significant impact.

In 1700 Liverpool was a fishing port with a population of 5,000 people. By 1800, 78,000 people lived and worked in Liverpool.

Thousands found work because of the trade in enslaved people:

- Ships were needed which had to be built and equipped.

- Carpenters, rope makers, dock workers and sailors were all in demand.

- Others found work in banking and insurance.

Liverpool was prosperous and booming, and its success was the result of its involvement in the trade in enslaved Africans.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYBristol and the trade in enslaved Africans

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYYet another port on the west coast of Britain, Bristol boomed because of its success in trading enslaved people.

Merchants, such as Edward Colston, spent money on fine new buildings in the centre of the city and invested heavily in education.

Industries such as copper-smelting, sugar-refining, and glass-making grew as a result of the trade in enslaved Africans as these goods could be exported in the first leg of the Triangular Trade â known as the Manufactured Run.

In 2020, the statue of Edward Colston was pulled down by protestors and thrown into Bristol's harbour. There has been discussions in the city about how the city acknowledges the historical role of its citizens in the trade in enslaved Africans.

One plan discussed was the commissioning of a public plaque that explained the city's links to slavery.

Image source, ALAMY

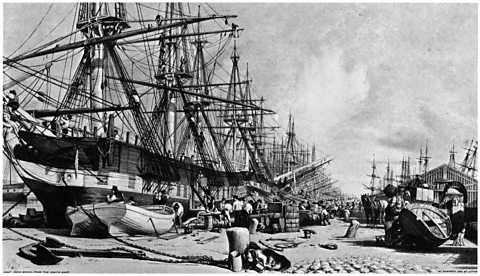

Image source, ALAMYLondon and the trade in enslaved Africans

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYLondon's ports played a prominent role in the trade in enslaved people.

From 1663-1698, London was the only British port that was allowed to trade in enslaved Africans. Slave ships destined for Africa would leave London loaded with goods to trade once they arrived.

The ports of London also handled and processed most of the sugar that was brought from the Caribbean.

Such was the volume of goods coming into London, that they needed to construct a new dock, the West India Docks.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYSlavery and London's banks

With the rise of other ports on the west coast of Britain, Londonâs traders began to look for other means to make money.

This led to the development of Londonâs major financial centre, known as the City of London, and witnessed the birth of many major banks and financial institutions that are still with us today.

- Lloydâs of London: Lloyd's of London has its roots in transatlantic trade linked to enslaved people. The profits made from insuring slave ships allowed it to grow into one of the worldâs largest banking and insurance houses.

- Barclays Bank: David and Alexander Barclay made vast amounts of money from the transatlantic slave trade. They set up Barclays Bank in order to provide loans to other merchants.

- The Bank of England: The bank was established in 1694. It provided finance for slave traders and plantation owners. Some of the top people in the bank also owned plantations in the West Indies.

Test what you have learned

Quiz

Recap what you have learned

From this guide you know that British ports were very important in the development of the trade in enslaved Africans.

- London's ports handled sugar imports from Caribbean plantations.

- London financial institutions and banks made money from funding and insuring the trade in enslaved people.

- Glasgow controlled 50% of the European tobacco trade.

- Bristol's industries provided goods to trade for enslaved Africans. It was also a major sugar port.

- Liverpool merchants carried more enslaved Africans than any other British port â around 60% of the trade.

As well as carrying enslaved Africans, British ports benefitted from the trade in other ways. Many ports carried and traded good created by enslaved workers.

More on Trade in enslaved African people

Find out more by working through a topic

- count4 of 10

- count5 of 10

- count6 of 10