How was propaganda used in the war?

Many young men who joined up to fight in World War I thought that it would be a brief and glorious adventure – they felt they were doing the right thing for their family and friends.

Governments produced propaganda in order to spread a particular political message. When World War One (WW1) broke out, the British government didn’t want people to think about the violence and death that would occur.

As they needed lots of people to volunteer to fight in the war, they portrayed it in a patriotic way - so people would see it as their duty to sign up. Repeated over and over again, the distortion of reality worked - 2.5 million men volunteered without knowing that 1 in 10 of them would not return home.

Pals Battalions

Many nations today legally require their citizens to serve in the military. This policy is called conscription. While most other countries used conscription to increase the size of their armies in the lead up to the war, Britain’s army was entirely made up of volunteers.

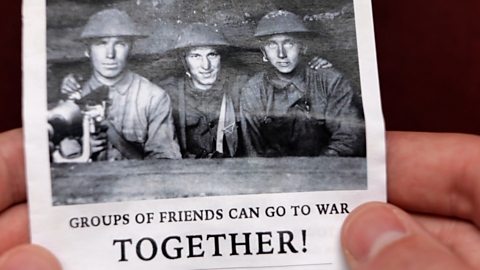

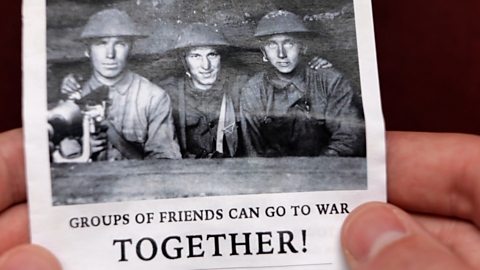

The government’s refusal to implement conscription posed a problem. How were they going to rival the mass conscripted armies of other nations? The government employed a clever campaign to swell its army’s size and attract men to enlist by allowing them to serve alongside their friends, relatives and workmates - in units that later became known as Pals Battalions.

Instilling a strong sense of community and fear of missing out, however misleading it may have been - worked! In 1914, thousands of men volunteered for military service and many formed Pals Battalions with people in their local community.

Under the government’s propaganda campaign, between August 1914 and June 1916, 145 Pals Battalions were formed, along with 70 reserve units. Units from cities including Manchester, Leeds, Newcastle, Hull, Glasgow and Edinburgh joined in their thousands.

While many citizens volunteered individually, the Pals Battalions represented over one-fifth of new infantry battalions created during this period of time.

It is difficult to say whether many of the men who joined a battalion wanted to join of their own accord. As initial enthusiasm and patriotic fervour lessened, much of the government’s recruitment drive applied immense social and peer pressure, shaming able-bodied men who hadn’t yet fulfilled their so-called duty.

Since many of the battalions were made up of volunteers, most Pals Battalions spent the first two years of the war training in Britain. For most of the volunteers, their first major offensive was in north France in 1916 - at what became known as the Battle of the Somme.

For many in the Pals Battalions, their first battle would be their last. The first day of the Somme was disastrous. The preceding artillery barrage had not been successful in inflicting damage on the German trenches with many of the barbed wire defences still intact. Military commanders, concerned with maintaining discipline in their new volunteer army, instructed them to walk in formation towards German lines when the attack began.

As a result of the Battle of the Somme, there was around 60,000 casualties, of which 20,000 were dead. Many units sustained heavy casualties, which caused untold hardship and suffering in their local communities. For example, the Leeds Pals lost around 750 of their 900 participants. Of the 720 Accrington Pals, 584 were killed, wounded or missing in the attack. The Grimsby Chums and the Sheffield City Battalion lost approximately half their members.

Conscription

After the Battle of the Somme, the experiment of the Pals Battalions was not repeated again by the British government. The government found it hard to find more volunteers to join the army as the general public started to come to terms with the trauma, death and suffering of the previous two years of war. The government struggled to appeal to people’s patriotism when so many were mourning the lives already lost.

The debate over conscription resurged again. Those against conscription argued that requiring people to join the army without choice meant another increase in the power of the government at the cost of individual liberty. Supporters of the policy argued that it was the duty of every young man to defend their country above all else.

The government knew that the war wasn’t going to end anytime soon and that there were going to be lots more casualties. So, in January 1916, the government passed the Military Service Act, which began the process of conscription.

Military Services Act

If their names were selected, the law required people to join the army for the duration of the war. At first, only single men between the ages of 18 and 41 were conscripted. As the casualties mounted up and the war prolonged, conscription was extended to married men in May 1916 and to those up to the age of 50. These men did not volunteer - they were forced to join.

Various factors could exempt a man from service according to the Military Services Act:

- Age

- Occupation

- Ill-health

- Conscientious objection

The Act excused essential workers such as coal miners, but, according to the law, every man was legally born a soldier, waiting for his call-up papers.

Resistance to conscription

Thousands marched in protest, citing previous arguments of infringement to personal liberty. Thousands of people applied for exemptions, which created endless tribunals on whether someone should go to war or not.

By the end of 1916, more than a million men had been called up and went, willingly or not. In April 1916 over 200,000 protested against the Military Service Act in Trafalgar Square in London.

Some of the men who failed to overturn their conscription at a tribunal still refused to participate in military service - often, such men were sent to prison. Others compromised on their refusal to take up arms and were willing to go to war to act as stretcher-bearers. Sadly, many stretcher-bearers were killed doing this job.

Human cost

- Despite the resistance against conscription, 1.1 million people were enlisted in the first year

- During the whole of the war, 2.5 million people were forced to join the war

- Across the world, the human cost of WW1 was enormous. An estimated 12 million civilians died, while more than 9 million soldiers were killed

- Those soldiers that did survive did not walk away unscathed. The war left 21 million military men wounded, many of them with life-changing injuries and mental traumas.

Test yourself

More on World War One

Find out more by working through a topic

- count3 of 5

- count1 of 5