The Aftermath of the Easter Rising

On 29th April 1916, a crowd of curious Dubliners watched as a large group of men in the uniform of Irish Volunteers was led away by British soldiers. The locals reacted angrily, jeering the men.

They were furious for a number of reasons:

- Dublin had been brought to a standstill for a week;

- the city centre was a smouldering ruin;

- 450 people, including 38 children, had lost their lives;

- women could not collect their war pensions.

However, within six weeks, the same rebels would be celebrated in a way few could have imagined possible. Those who had witnessed the surrender of the rebels had no idea that a chain of events had begun that would eventually see Ireland split in two with British Rule ended in one part.

Watch as Max Heartrate explains how we ended up with two countries on a tiny little island like this one

DIRECTOR: Standby on the floor.

DIRECTOR: Coming to you camera two.

DIRECTOR: Cue on two.

DIRECTOR: Mix-through.

MAX: No time for that! Hello! Iâm Max Heartrate and this is Knowledge Express. Information faster than a wasp on a water slide. And todayâs topic isâŠ

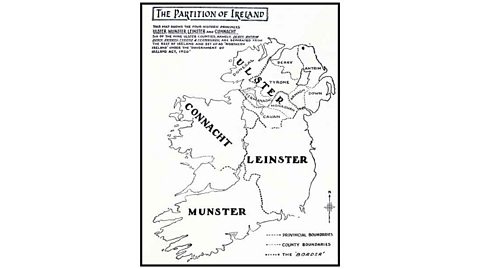

MAX: So, The Partition of Ireland. Exactly how did we end up with two countries on a tiny little island like this one? Well, itâs a long story

MAX: and we donât do long stories on Knowledge Express, but letâs give it a go.

MAX: So, itâs the late 19th century and some people are starting to think that maybe Britain shouldnât rule Ireland.

MAX: These âIrish Republicansâ want it back and 1916 they decide to take it back⊠by force. But the British army doesnât take long to defeat the rebellion. Most Irish people actually donât much like the rebels of 1916 or the violence.

MAX: However, that all changes when the British government decides to execute sixteen of the ringleaders. Horror. Outrage. Everything is now changed, changed utterly. From that moment things go from bad to worse for the British government in Ireland.

MAX: In 1919, Sinn FĂ©in sets up a provisional government in Dublin. At the same time the Irish Republican Army starts a war against the British. In the hope of a solution the British create the Government of Ireland Act. The island is divided into Northern Ireland (the six northern counties) and Southern Ireland (the other 26 soon to become the Irish Free State.) Bish, bosh, draw up a border to keep things right and bingo! Everyone happy?

MAX: No! Many southern Nationalists are disgusted at giving up the six northern counties. Northern Nationalists feel betrayed and vulnerable. Who knew international political negotiations could be so complicated! Do ye know what I mean like?

The Constitutional Nationalist Tradition

- When this rebellion took place, World War One had been going on for more than a year and a half.

- Over 170,000 Irishmen were fighting for the British army against Germany.

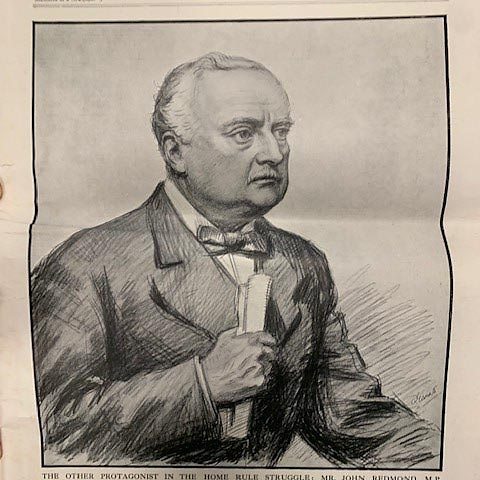

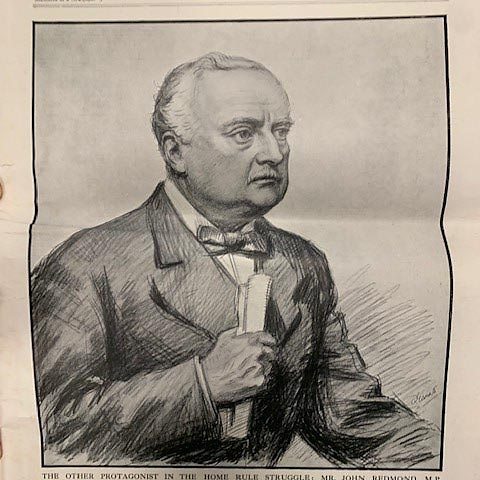

- Almost 90% of the Irish Volunteer force (IVF), the paramilitary group set up to ensure the implementation of ±«Óătv RuleThe idea that Ireland should have a parliament to look after local issues. , had followed the call of John Redmond, the Nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) leader to âgo wherever the firing line extends.â

Redmond was part of the Constitutional Nationalist tradition. Constitutional Nationalists used politics to achieve greater Irish independence and were against the use of force.

This was supported by the vast majority of Irish Nationalists and their campaign seemed to be working given that ±«Óătv Rule had been passed into law, even though it had not yet been implemented, due to the start of the War.

What do you know about the Physical Force Tradition?

Apart from Constitutional Nationalism, there was another, much smaller side to Nationalism, the Physical ForceThose Nationalists who supported the idea of violent rebellion as a way to end British control over Ireland. tradition, which believed that independence could be achieved through violence.

There had been several attempts to put this theory into practice, but these had failed due to a lack of support among the population and the overwhelming strength of their opponent.

A secretive organisation

A small group remained committed to this strategy.

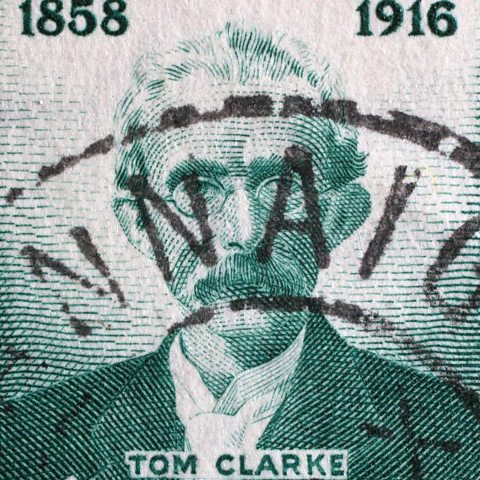

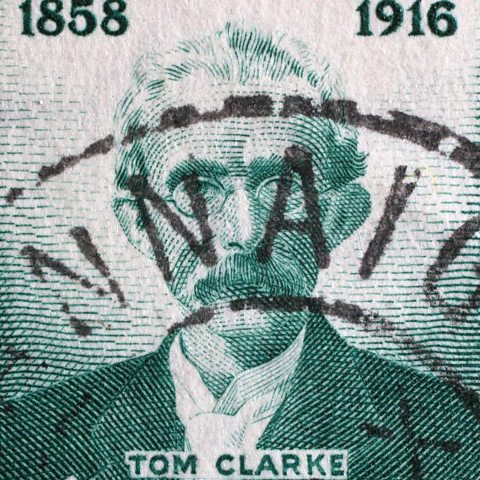

In 1907 a man named Thomas Clarke opened a tobacconist shop in Dublin.

Clarke had spent 15 years in prison in England for his part in the 1883 assassination of a British official. He then spent ten years working in America with Clan naGael, a group of exiled FeniansAn earlier name for Physical Force Nationalists. .

The shop was actually a frontA person or organization acting as a cover for subversive or illegal activities.. Clarke was on the leadership committee of a small, secretive organisation, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), funded by Clan naGael with the express intention of planning a major rebellion in Ireland.

Planning a rebellion

The IRB leadership, which included radical poet Padraig Pearse, knew that a successful rebellion would rely on three things.

| Timing | There was an old saying within the Physical Force tradition that âEnglandâs difficulty was Irelandâs opportunityâ. Britain was preoccupied with the War and its army in Ireland was a fraction of the size it would have been during peace time. |

| Rebels | The IRB would have no chance of overcoming, even a vastly reduced British force. They planned to use the 10,000 Irish Volunteers who had rejected Redmondâs call to fight in the War and stayed at home, loyal to Eoin MacNeillThe founder of the Irish Volunteers.. The IRB had members on this group's committee and planned to convince MacNeill that a rising was necessary. |

| Weapons | Clan naGael had purchased weapons from Germany. These were to be delivered on board a ship called the Aud. |

An heroic failure?

The date set for rebellion was Easter Sunday, 23rd April 1916. However the original plans ended in disaster.

- The Aud was captured by the British navy and its weapons sent to the bottom of the sea.

- MacNeill found out that he was being used by the IRB and, in order to stop the planned rebellion, placed a message in the Sunday Independent, telling Volunteers not to participate.

Despite their plans being in ruins, the IRB decided the rising would go ahead on Easter Monday.

Their chances of success were extremely slim; however, Pearse believed that even if they were captured or killed, their âblood sacrificeâ might inspire others.

- Approximately 1,500 rebels, made up of Irish Volunteers, IRB members and members of the Irish Citizen Armya small paramilitary group of Irish Transport and General Workers Union members, established to protect members from police actions took up defensive positions around Dublin.

- Puzzled onlookers listened as Pearse read out the âProclamation of the Republicâ on the steps of the General Post Office, the rebelsâ headquarters.

- Over the course of the next week there were skirmishes between the rebels and the authorities, but once British reinforcements arrived there could only be one outcome and the rebels surrendered on Saturday 29th April.

With the rebellion over, it looked as if the events of Easter 1916 would be added to the long list of Physical Force Nationalismâs âheroic failuresâ. That it was not was more the result of the reaction of the authorities than the actions of the rebels themselves.

- In its aftermath the press called the Easter Rising the Sinn FĂ©in rebellion - after a small anti-British political party operating in Dublin. This was a mistake, but it played a key part in the growing support for Sinn FĂ©in as a consequence of the executions that followed the Rising.

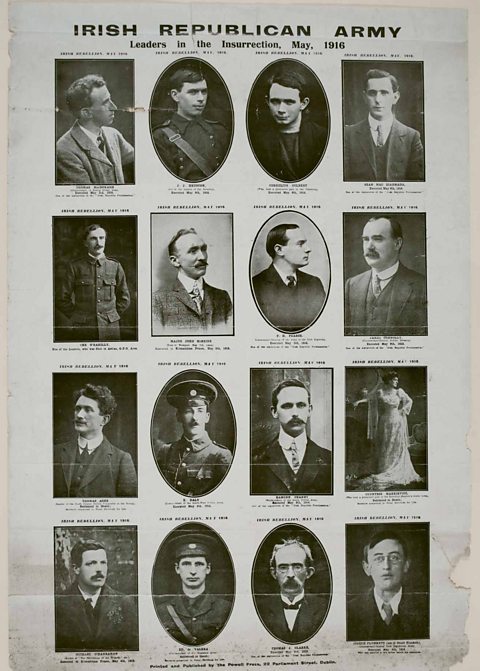

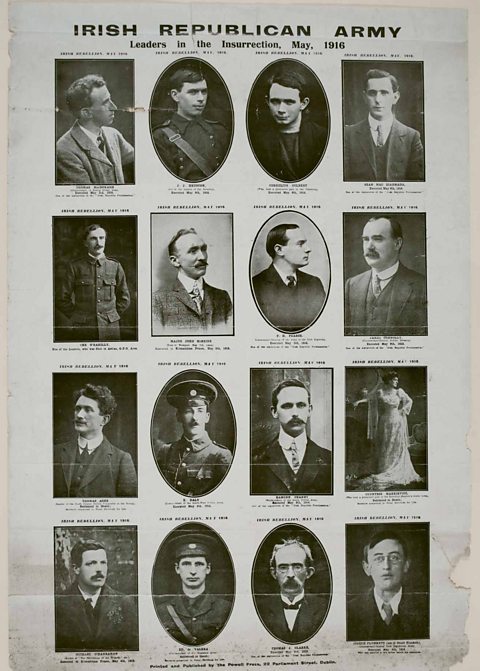

- Between 3rd and 13th May 1916, 15 rebels - including all seven signatories of the âProclamationâ - were executed in Kilmainham Jail.

- The main consequence of these executions was outrage at the British actions - and an increase in support for those associated with the Rising.

Why did Sinn FĂ©in become so popular?

Key points about Sinn FĂ©inâs rising popularity:

- Public outrage at the British reaction to the Rising.

- Increasing frustration that ±«Óătv Rule had still not been delivered, long after it had passed through Parliament.

- The reason for this delay was World War One and this too was becoming unpopular, as the initial enthusiasm to join up met the grim reality of death.

- The British army was running short of men and there were plans to introduce conscriptionCompulsory military service. to Ireland. This met with huge opposition from all shades of Nationalism and also the Catholic church. Sinn FĂ©in led this opposition.

Conscription proved a difficult issue for the IPP, given that its leader, John Redmond had actively encouraged Irishmen to join the war effort.

The resulting Conscription Crisis was an indication that Sinn FĂ©in, rather than the IPP, was now leading Irish Nationalism. This was borne out in the 1918 General Election that followed the end of the War.

- Sinn FĂ©in won 73 seats.

- The IPP won six seats.

It was clear that ±«Óătv Rule was now a thing of the past. Full independence was now the goal of Irish Nationalism.

Key events leading to warfare in Ireland

Sinn FĂ©in was led by Ăamon de Valera. Its newly-elected MPs refused to attend Westminster and instead set up their own parliament, DĂĄil Ăireann, which they insisted was the rightful authority of the Irish Republic.

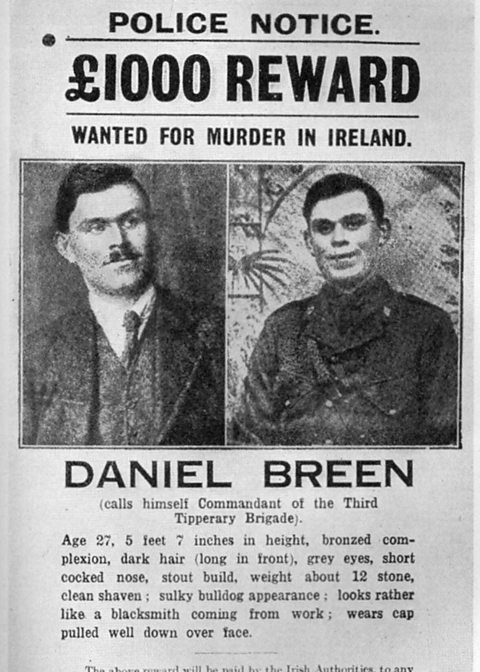

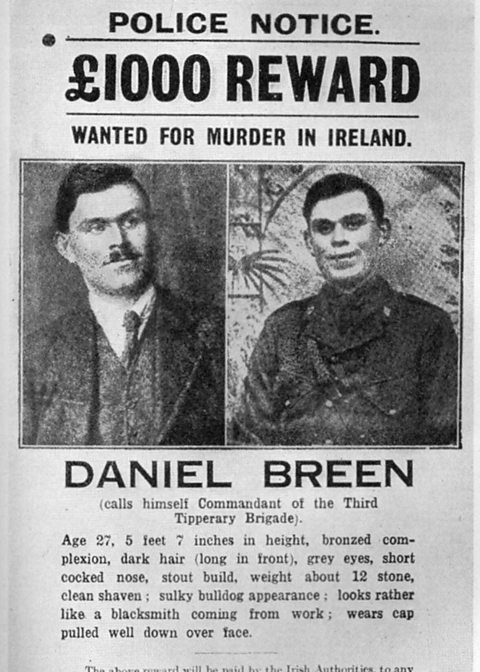

- DĂĄil Ăireann met for the first time on 21st January 1919. On the same day two members of the police, the RICThe Royal Irish Constabulary was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, were shot dead in County Tipperary by a Republican called Dan Breen. These murders were only the first in a long series of guerrilla warfareA type of warfare that uses unusual tactics, and in-depth knowledge of local surroundings, to defeat opponents both physically and psychologically. style âhit and runâ attacks on members of the RIC and those that worked for the British government.

- Those responsible for the killings called themselves the Irish Republican Army (IRA). They were directed by Michael Collins, an increasingly prominent member of the Republican movement. There were clear links between the IRA - which had emerged from those Irish Volunteers responsible for the Easter Rising - and DĂĄil Ăireann.

- Britain responded by sending in reserve forces to support the RIC. There were two such groups, the Auxiliaries and the Black and Tans. They were mainly World War One veterans who were poorly prepared to work in a civilian situation. They often carried out ill-disciplined attacks against the local population.

- Their behaviour made people angry and led to a growth in support for the IRA.

- This pattern of violence would be repeated for almost 18 months. On one Sunday alone in November 1920 the IRA killed 11 British agents and in response the British killed 12 people and wounded 50 others in Croke Park.

Finally, under pressure from public opinion in England, the government of Prime Minister David Lloyd George agreed a truce with Sinn FĂ©in in July 1921, to be followed by negotiations.

Partition

By this stage the British government had decided that it was not prepared to force Ulster Unionists to accept ±«Óătv Rule. The Unionist position had been strengthened by the fact that so many of its supporters had died fighting for Britain at the Battle of the Somme.

This decision was reaffirmed in the 1920 Government of Ireland Act, which created Northern Ireland. It would consist of six counties (the historic Ulster counties of Monaghan, Cavan and Donegal were not included). The new Northern Ireland Parliament was opened by King George V in June 1921.

It was against this backdrop that the Sinn FĂ©in negotiation team, led by Collins, arrived in London to discuss a settlement. They were not interested in ±«Óătv Rule; they wanted a full Republic.

They were not offered this. Instead, an independent Irish Free State consisting of the remaining 26 counties was proposed. It would remain part of the British Empire and members of its parliament would have to swear an Oath of Loyalty to the monarch. The negotiators were also offered a Boundary Commission to review partition at some future date.

Knowing that they could not restart hostilities, the Irish delegation signed the Treaty. It proved controversial among Republicans, particularly the Oath of Allegiance. In the end the DĂĄil voted narrowly to accept the Treaty, but its opponents, led by Ăamon de Valera, walked out as a result.

The Irish public later backed the Treaty in an election, but the split among the Republicans led to a bitter Civil War (1922-1923), which was won by the supporters of the Treaty.

Meanwhile, the new government in Northern Ireland, led by Sir James Craig, was not prepared to participate in any review of partition. Partition thus became permanent and the two parts of Ireland set off into the future on very different paths.

Activity: Partition of Ireland

More on Northern Ireland in the early 20th Century

Find out more by working through a topic

- count1 of 2