Key points

- From the 1770s in Britain, a movement developed to bring the slave trade to an end. This is known as the abolitionist movement.

- The work of politicians, ordinary workers, women and the testimonies of formerly enslaved people all contributed to the British abolitionist movement.

- In 1807, the British Parliament passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act. This ended the buying and selling of enslaved people within the British Empire, but it did not protect those already enslaved. Many enslavers continued to trade illegally.

- Hundreds of thousands of people remained enslaved. It took a further 30 years of campaigning before slavery was abolished in most British colonies.

Video about the abolition of the slave trade

Narrator: In the 18th century, the movement to end the slave trade emerged. In Britain a powerful abolition movement inspired by activists and politicians from around the world began to bring about change.

Olaudah Equiano: I was enslaved for many years in the West Indies and America. I bought my freedom in 1766 and settled in Britain. I became friends with many of the British abolitionists such as Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson. They encouraged me to write my autobiography and I travelled the country giving talks about my experiences and telling people first-hand about the horrors of slavery.

Toussaint Louverture: In Saint-Domingue I led the fight for our freedom from French oppression and enslavement, but also for the recognition that we were equal to the Europeans. Our struggle inspired others around the world that they too could be free from the slave trade and colonial control.

Lord Grenville: It was a long battle. There were hundreds of petitions to Parliament led by William Wilberforce and his allies. People from all over the country had signed over 500 petitions. In 1807 I was the prime minister when Parliament finally passed the Slave Trade Act, which abolished the buying and selling of human beings.

Mary Prince: But this was not the end of the struggle. While it was illegal to buy and sell people, the brutal practice of slavery continued in plantations across the Caribbean. I was the first Black woman to publish my experiences and it helped push towards the Emancipation Act of 1833, which abolished slavery in most parts of the British Empire. But although people were legally free, the law required formerly enslaved people to keep working on the plantations but they were now called apprentices. They were often treated as harshly as before.

Narrator: These are just a few of the people who helped abolish slavery and there are many others who played important roles.

British campaigners for the abolition of the slave trade

The campaign to abolishTo officially end something. the slave trade began in the late 1700s. Several key groups and individuals were involved in the public campaign.

Politicians

Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp were leading abolitionists who fought to end slavery. In 1787, they established the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, whose purpose was to campaign for the slave trade to be brought to an end.

William Wilberforce was a member of parliament, and another key figure in the abolitionist movement. Although his proposals met with fierce resistance, from 1789 Wilberforce began to introduce anti-slavery motions in Parliament. He continued to do so until 1807, when the British Parliament introduced the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act.

Quakers

Nine of the twelve members of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade were QuakerA religious movement, founded by George Fox which stems from Christianity., formerly known as the Society of Friends. The Quaker Church strongly opposed the slave trade in Britain and America. In 1783, the London Society of Friends sent a petition against the slave trade to the British Parliament.

Working-class people

Working-class people in Britain also played a key role in calling for abolition. Despite benefiting from economic links to the slave trade, many workers in the port cities of Liverpool and Bristol signed petitions that were presented to Parliament. Over 500 petitions, with a combined total of around 390,000 signatures, were submitted in support of Wilberforceâs abolition bill in 1792.

Formerly enslaved campaigners for the abolition of the slave trade

Enslaved people found ways to demonstrate their resistance. The successful revolts by enslaved people in Barbados, Jamaica and Demerara shocked the British government. They knew that if enslaved people were not emancipatedTo be freed from the status of an enslaved person., large scale rebellions would continue. In 1838, enslaved people were finally emancipated after many years of fighting for their freedom.

The following people were all formerly enslaved. They played a key role in the British abolitionist movement by forming societies, sharing their stories and petitioning Parliament.

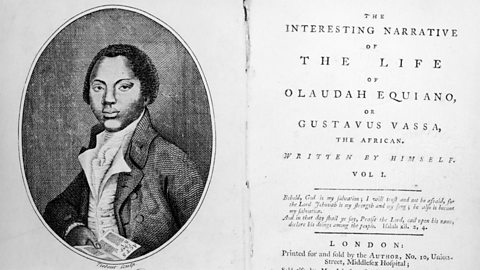

Image caption, Olaudah Equiano was sold to many enslavers in the Americas before being bought by Robert King. King promised Equiano that if he could raise the money King had bought him for, he would grant his freedom. By 1766, Equiano had raised enough money and was released. He settled in London and became vocal in the abolition campaign, befriending other formerly enslaved Black Britons and forming a group called the Sons of Africa. They were a group of formerly enslaved African men living in London, and played a key role in the abolitionist movement. In 1789, Equiano published his autobiography, sharing his experiences of enslavement.

Image caption, Ottobah Cugoano was born around 1757 in modern-day Ghana. Aged 13, he was captured and enslaved on the island of Grenada. In 1772, Cugoano was brought to Britain, baptised, and given his freedom. He worked as a servant for an artist who painted portraits of the wealthiest members of Georgian society. He met the Prince of Wales, who later became King George VI. This portrait is believed to be of Cugoano, and shows him with two English painters, Richard and Maria Cosway. Cugoano became a prominent member of the Sons of Africa group, demanding a total abolition of the slave trade.

Image caption, Phillis Wheatley was captured in West Africa and enslaved in Boston, North America. Wheatley was a talented poet. Unable to find a publisher in America, she travelled to London, where her account of the Middle Passage became a bestseller and contributed to the abolitionist campaign. Following her emancipation in 1775, she returned to America and got married. Wheatley continued to write poems, but she lived a life of poverty, and died at the age of 31.

1 of 3

An overview of the journey towards abolition

The journey towards abolition in detail

1772: The Somerset Case

James Somerset had been enslaved as a young man and taken to Virginia. He was bought and sent to London in the 1770s, but he escaped after two years. He was captured again and forced onto a ship that was heading for the Caribbean.

Somerset asked for the help of Granville Sharp. Sharp used Somersetâs situation to test the rights of enslaved people in Britain. He argued that no enslaved person in England could be forcibly moved and resold. In 1772, the judge, Lord Mansfield ruled that âno master ever was allowed here (England) to take a slave by force to be sold abroadBecause he deserted from his service, therefore the man must be dischargedâ.

In this landmark case, James Somerset was granted his freedom and other enslaved people in Britain could not be shipped back to the Caribbean. However, this did not result in emancipationThe process of being set free from enslavement.. It wasnât until 1807 that enslaved people in Britain were granted their freedom.

1781: The Zong Case

The Zong was an overcrowded ship that carried enslaved Africans to the Americas in 1781.

Due to a navigational error, the ship had to spend an additional three days at sea.

With supplies and water running out, the crew murdered 131 enslaved people by throwing them overboard. If they had died onboard the ship, the crew would not have been able to make an insurance claim for compensation. The case was used by abolitionists such as Olaudah Equiano and Thomas Clarkson in order to highlight the extreme brutality of the traders in enslaved people.

1787: Ottobah Cugoano shares his experiences of enslavement

In 1787, Ottobah Cugoano, published his essay Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evils of Slavery. This was the first published critique of the slave trade by an African person. Cugoanoâs essay served as a powerful testament to the horrors of enslavement.

1780s: Primary evidence

In 1789, the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade persuaded William Wilberforce to represent them in Parliament. Thomas Clarkson collected information for the committee to present to Parliament and the public. He travelled around Britain, making visits to the ports of Liverpool and Bristol, gathering evidence about the slave trade from eyewitnesses, including from sailors who had worked on slave trading ships.

1789: Olaudah Equiano's autobiography

In 1789, Equiano published his autobiography, which detailed his experiences of enslavement. Equiano embarked on a lecture tour through Ireland, Scotland and England to share his story.

1792: Petitions to Parliament

In 1792, over 519 petitions with thousands of signatures were handed to Parliament. Alongside these petitions, William Wilberforce presented a bill for the abolition of the slave trade every year, from 1789 to 1807.

1791 - 1792: Sugar boycotts

From 1791 - 1792, 300,000 people, most of whom were women, became involved in the boycotting of sugar and other goods produced using enslaved labour. One of the women involved in the boycotts was Hannah Moore, a passionate anti-slavery campaigner from Bristol who encouraged other women to join the abolitionist movement. This led to a dramatic decrease in sugar sales, directly affecting the profits of plantation owners.

1804: Haiti becomes a republic

In 1791, a rebellion against enslavement occurred in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. In 1804, Saint-Domingue became the independent Republic of Haiti. Those who used the labour of enslaved people became afraid that rebellions might start to happen more often. These fears became a factor in the eventual decision to abolish the slave trade.

The 1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade Act

After over twenty years of campaigning, the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed by the British Parliament in 1807. The Act made it illegal to buy and sell enslaved people throughout the British colonies.

However, while the act abolished the trade in enslaved people, it did not end the use of enslaved labour across the British Empire. Plantation owners were still able to use their existing enslaved labour force.

This meant that some people in the Caribbean, and elsewhere in the British Empire, remained enslaved.

Why didnât the 1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade Act end the use of enslaved labour across the British Empire?

A considerable part of Britainâs wealth was dependent on the products produced by enslaved people. The sale of exported goods such as sugar and tobacco helped to sustain the British economy.

Many plantation owners were British, and had ties to influential figures in British politics. Some were even members of parliament themselves, such as George Hibbert and William Beckford. These people opposed the abolition movement and were known as the West India Lobby. An end to enslavement would mean having to pay their plantation workers, which would significantly reduce their profits. They used a range of tactics to spread a pro-enslavement message.

Hibbert and Beckford produced pamphlets explaining why the slave trade was necessary. They argued that the economy of the British Empire was reliant on the slave trade and that it would collapse without it. They also lobbied Parliament, using their power to put pressure on others, and their wealth enabled them to buy votes.

As a result of this opposition, abolitionists decided to focus on the campaign to end the trade in enslaved people from Africa. They hoped that this would lead to the gradual end of all slavery across the British Empire.

Activity - Put the events in order

How did enslaved people fight for their freedom?

While the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was a significant milestone, it did little for the thousands of people still enslaved across the British Empire. Alongside the abolitionist movement in Britain, it was the resistance of enslaved people that was a very significant factor in their emancipationThe process of being set free from enslavement..

Between 1675 and 1797 there were hundreds of rebellions by enslaved people in the Americas.

The FĂ©don's rebellion began in 1795 on the island of Grenada. Julien FĂ©don, a free man, wanted to end both slavery and British rule in Grenada. He led a group of 100 free people who attacked cities in Grenada, burning properties and looting. The rebellion grew over time and lasted around 15 months. By the end of the fighting, in June 1796, FĂ©don was defeated and approximately 7000 enslaved people had died. 50 rebels were captured, with 30 executed for treason.

In 1815, a rumour had swept through Barbados that the governor would soon provide the enslaved population with papers to emancipate them. This didnât happen. In 1816, a man named Bussa led 400 men to fight for their freedom. In the aftermath, 300 enslaved people were taken to Bridgetown for trial. 144 were executed, and 132 sent to other islands for fear that they might begin another rebellion on Barbados.

In 1831, workers from plantations in Jamaica began to strike. During the Christmas Rebellion, also known as the Baptist War, enslaved people refused to work. They hoped that it would force the plantation owners to pay them or risk the spoiling of their sugar crops. It developed into an open rebellion, led by Sam Sharpe.

It is estimated that around 60,000 enslaved people rose up across 200 plantations. It took 11 days for the British Forces to suppress the uprising. In the aftermath, the Jamaican colonial government and the leaders of Jamaica brutally punished those involved. Sam Sharpe was publicly executed, along with 138 others. This violence and brutality shocked some in Britain, who questioned the reaction of the Governor of Jamaica.

Slavery Abolition Act 1833

The abolition of enslavement in the British Empire was not wholly achieved until the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. Protecting profit remained a crucial factor in ending enslaved labour in the colonies. When Britain abolished the practice of enslavement, plantation owners across the British Empire received a share of ÂŁ20 million, around ÂŁ17 billion in today's money, in compensationSomething awarded to someone in recognition of loss.. In contrast, the newly emancipated people received no compensation and were forced into a new apprenticeship scheme, which tied them to their plantations for up to six further years.

In reality, little had changed for enslaved people. They were still expected to work ten-hour days, and punishments such as floggingBeating a person severely with a whip or stick. were still allowed. These apprenticeships were ended in 1838, when emancipation was finally achieved. Across the Caribbean, enslaved people held ceremonies, with some even holding funerals to try to bury the memories of enslavement.

Test your knowledge

Play the History Detectives game! gamePlay the History Detectives game!

Analyse and evaluate evidence to uncover some of historyâs burning questions in this game.

More on The transatlantic slave trade

Find out more by working through a topic

- count1 of 3

- count2 of 3