Andreas Vesalius, Ambroise Paré and William Harvey

A few individuals, such as Andreas Vesalius, Ambroise Paré and William Harvey, made particularly important contributions to medical knowledge during the 16th and 17th centuries.

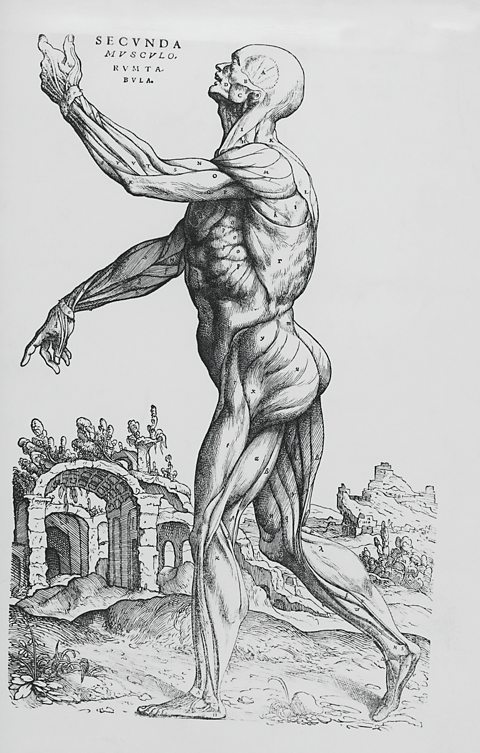

Andreas Vesalius

Vesaliusâ greatest contribution was in the field of anatomy.

Before Vesalius, doctors relied on the works of Galen and other ancient writers. However, Galen had only dissected the bodies of animals, cutting them up to study them, and their bodies were different from humans.

In 1537, aged just 22, Vesalius became professor of medicine at the University of Padua. He insisted that his medical students should perform dissections to find out how the human body worked.

A local judge took an interest in Vesaliusâ work. He allowed Vesalius to use the bodies of executed criminals for dissection. Vesalius was then able to make repeated dissections of humans without any opposition.

In 1543, Vesalius published his book The Fabric of the Human Body. He employed artists to make accurate drawings of the human body. These gave doctors more detailed knowledge of human anatomy.

Vesalius proved that some of Galenâs ideas on anatomy were wrong. For example, Galen had claimed that the lower jaw was made up of two bones, not one.

Vesalius encouraged others to investigate for themselves and not just accept traditional teachings.

Ambroise Paré

Paré changed ideas about surgery.

Before Paré, wounds were treated by pouring boiling oil into them. To stop the bleeding, they were cauterised, ie sealed with a red-hot iron.

Paré began his career as an apprentice to his brother, a barber surgeon. In 1536 he became a surgeon in the French army, where he worked for 20 years. During this time he developed his ideas about surgery.

During one battle, supplies of cautery oil ran out. Instead, Paré used an ointment of egg yolk, oil of roses and turpentine, which had been used in Roman times. He found that the wounds treated with this mixture healed better than those treated with boiling oil.

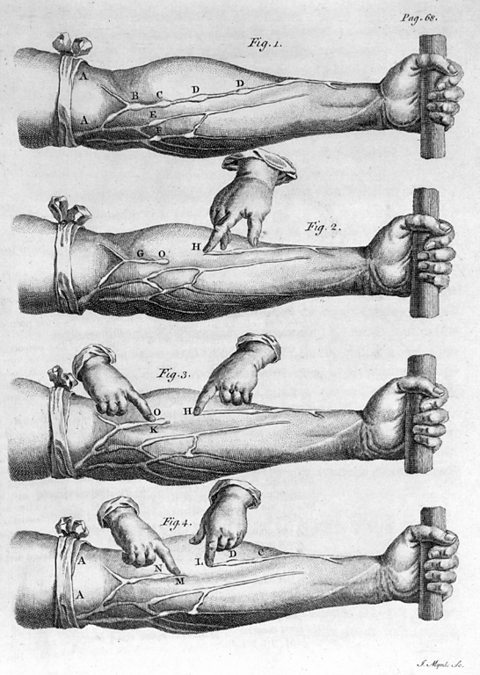

During amputations, instead of cauterising, he used ligatures such as silk threads to tie blood vessels. Unfortunately, ligatures did not reduce the death rate. Dirty surgeonsâ hands and contaminated ligatures caused infections in the wounds being treated.

In 1575, Paré published his book Works on Surgery. It proposed changes to the way surgeons treated wounds and amputations.

William Harvey

Harvey discovered the principle of the circulation of the blood through the body.

Before Harvey, doctors accepted Galenâs idea that new blood was manufactured by the liver to replace blood that had been burned up by the muscles.

Harvey became physician to James I (and later to Charles I). Both kings were interested in science and encouraged Harveyâs research.

Harvey was also a lecturer in anatomy. He dissected animals and carried out experiments to build up a detailed knowledge of the working of the cardiovascular system (the heart and blood vessels). This led him to reject Galenâs ideas.

In 1628 he published An Anatomical Account of the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals. In this book, he proved that the heart acts like a pump and is responsible for recirculating the blood around the body.