Imagine how heavy 250 buses piled on top of one another would be - thatâs the same weight as the 3,000 metric tonnes of vanilla that was exported around the world in 2023.

Vanilla is so commonly used as a flavouring in everything, from ice cream to perfume, that it's become part of everyday life.

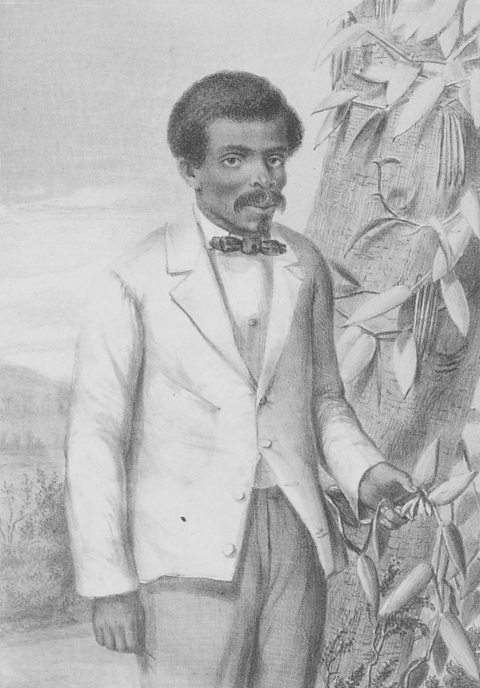

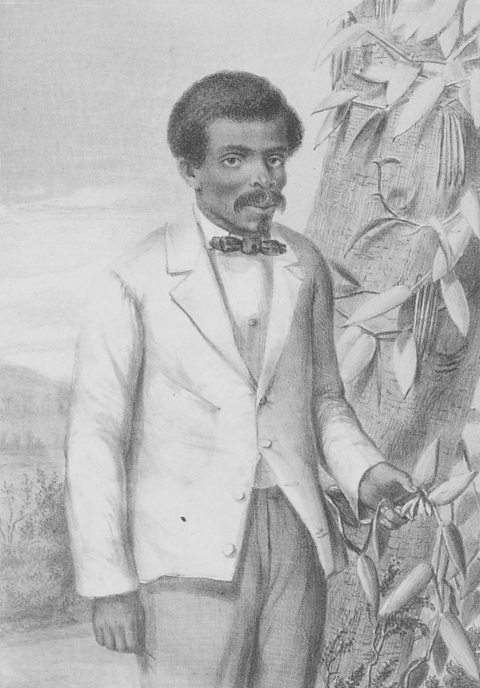

But thereâs nothing everyday about the story of how the spice became so widely available - all thanks to a 12-year-old boy called Edmond Albius.

Who was Edmond Albius?

In 1829, Edmond was born into slavery on the island of Bourbon (now called RĂ©union), a French colony.

He did not know his father, Pamphile, and his mother, Melise, had died in childbirth by the time the boy was sent to French plantation owner Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont, who began teaching him about horticulture and botany.

When Bellier-Beaumont was walking through his gardens one day in 1841, he noticed something surprising - a pair of fruits on a vanilla vine. The plant was the only surviving vine of a number of cuttings that had been sent to him in the late 1810s.

In the more than two decades that had passed, he had failed to get it to bear fruit. So what had happened?

A whole new way of fertilisation

Edmond told Bellier-Beaumont that he had found a way of fertilising the vanilla flowers by hand, which he had based on a method for hand-pollinating watermelon plants that the plantation owner had previously shown him.

Vanilla flowers contain both female and male parts but, due to the way they grow, they are not able to self-pollinate. And to make things even more challenging, the bee species that is able to pollinate the flower only exists in Mexico.

Edmondâs discovery - that you could bring both parts in contact by hand - meant vanilla pods could be grown in other parts of the world.

A young boy's discovery still has an impact

Dr Leanne Melbourne, Exhibitions Officer and Researcher at Oxford University Museum of Natural History, learned about Edmond when working on a project for Black History Month to highlight the achievements of black people in natural history.

What appealed to her, she said, is âthe idea that someone of such a young age really had a big impact on something that we don't even think about to this day.

âWe have vanilla flavouring for everything. Itâs amazing to think that actually a 12-year-old boy was really instrumental in it being distributed all around the world.â

At the time, not everyone was convinced that Edmond could have made the discovery alone.

Leanne said there are several reasons for this: âAt this time, there were a lot of people who were coming up with the technique. There was a French botanist who did come up with a technique before Edmond, but it wasn't very easy to use and really needed controlled academic, scientific conditions.

âEdmond wasn't necessarily the first or the only person. It just so happened that where he did it and when he did it allowed the industry to flourish.â

There may also have been people who doubted that a boy of his age was experienced enough to develop the technique.

Leanne said: âI guess there was a level of, well, he's a 12-year-old boy. How does he know? We have all these people who've been studying this for years, and they should know better than a 12-year-old boy.â

Leanne added that some people may have thought that, because he was enslaved, Edmond didnât have the right skills or deserve recognition.

Why have so few people heard Edmondâs story?

Other planters visited Belle-vue plantation to witness Edmondâs pollinisation technique for themselves, and Edmond was taken around RĂ©union to demonstrate it to other enslaved people. His discovery led to an explosion of vanilla production on the island, which by 1898 was exporting 200 tonnes to France and outperforming Mexico as the worldâs largest producer.

Bellier-Beaumont made an effort to credit Edmond for his contribution - even arguing that he should receive a state pension for his services to the vanilla industry. But it wasnât enough.

By the time France abolished slavery in its colonies, and Edmond was freed, he was 19-years-old and struggling to find work. A job as a âkitchen boyâ in an officerâs house was cut short when he was imprisoned after a robbery took place there.

Thanks to appeals by Bellier-Beaumont, he was freed early and later married. He died at the age of 51.

Discovered in the archives

Edmond's story was forgotten until writer Tim Ecott uncovered information about his discovery while researching his book Vanilla: Travels in Search of the Luscious Substance, published in 2004.

Leanne says: âIf Tim Ecott had never gone into the archives, then we might not know Edmondâs story today.

âHistory remembers those who have the power, who have the ability to document their contributions. Natural history, which really took off in the 18th Century, started off as a very European Western pursuit of knowledge.

"A lot of the collecting happened in colonies so there are a lot of contributions from enslaved people and from indigenous people whose work probably wouldn't be documented.â

There are many other stories that are yet to be found in the archives, said Leanne.

âThere's still so many that we haven't discovered yet because we haven't looked at the right piece of paper that has a name on it or some kind of throwaway comment.

âFor example, Charles Darwin in his biography talks about being taught by a former enslaved person called John Edmonstone, and if he hadnât written this one little comment about who taught him The art of preparing animal skins, by stuffing them, so they resemble the creature for the purposes of display. we would never have known.â

This article was published in September 2024

How black history can be found in fashion

A well-cut suit, a comb and a t-shirt can have much to say about black people's lives.

Black History Month: Pioneers in British black history

Shining the spotlight on some of the inspirational black trailblazers in British history