History has milestones.

Significant dates and events stand as markers for a movement or era - from the abolition of slavery in the 19th Century to Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963.

But then there’s the history which is all around us, even if we don’t notice it. That could be in the clothes we wear, or even our hair style. To mark Black History Month, Professor Carol Tulloch of University of Arts London - an expert in fashion, textiles and cultural heritage - spoke to ±«Óătv Bitesize about the black history that can be found in something as straightforward as a suit - or even a comb.

The formal style of the Windrush generation

In 1948, a ship called Windrush docked in Essex, carrying passengers who were mainly from the Caribbean. This was the start of people from different parts of the Commonwealth settling in the UK to find employment opportunities in the years after the Second World War when new workers were needed in many jobs. They became known as the Windrush generation and they also brought with them an influential look.

Prof Tulloch said: “If you’re talking about Windrush and people arriving as passengers, there’s a lot of photographs of that time and the disembarkation of mainly men, and some women. They’re in incredibly beautiful suits and ties.”

These sharp suits, with trousers in different cuts than UK men were used to - often wider or slimmer in the leg - highly polished shoes, smart ties, immaculate haircuts and hats such as the fedora and trilby (with brims folded upwards), became part of what was later known as Black British Style. It wasn’t just about looking as smart as possible, as Prof Tulloch explained - it was also a move parents were keen to encourage in the hope their children would avoid prejudice. She said: “It was just drilled into you about looking the best you could when you went out on the streets. To look smart, to look presentable. You’re so well turned out that you don’t attract racism.”

Fabrics from the Caribbean and Africa were also in the ensemble. Winston Levy, father of the novelist Andrea Levy, had a shirt showing scenes of Jamaican life with him when he stepped from the Windrush, to remind him of home. It is now part of the British Library's collection.

The emerging Black British Style was noticed by the wider world. Prof Tulloch explained how some men who had been tailors in Jamaica now found themselves working for major UK menswear stores. They wouldn’t always work in the factory but from their bedrooms, sewing garments together before handing them over. The smart look which combined fabrics from UK and African cultures also influenced the A movement of people inspired by cultures beyond the UK mainstream in the 1950s and ’60s. movement. The designer Althea McNish was born in Trinidad, moved to the UK in the 1950s and became acclaimed for her colourful designs in the austerity of the post-war period. Her fabrics were often selected for couture designs by fashion houses such as Christian Dior.

The Afro - and its comb - as symbols of empowerment

In the 1960s and ’70s, the Black Power movement grew in the US. Its aim was to instil racial pride and create political and cultural institutions with black people, their history, and an empowered future at its heart, although in the USA some of its methods were seen as controversial by parts of American society. The movement also spread into the UK, with protests and marches organised in different parts of the country. A symbol linked to Black Power is the Afro hairstyle, where black people wore their hair naturally without smoothing it down, as had previously been commonplace. These styles could be so voluminous, a special kind of comb was needed to maintain it.

“The afro comb emerged as part of the black consciousness and Black Power movement,” said Prof Tulloch. “Firstly in the United States and then, all over the world.”

Prof Tulloch also commented on the difficulty she had buying products made specifically for Afro hair in her home town of Doncaster when she was a teenager in the 1970s. She laughed: “If I went to London to see my gran, I would have orders from friends of what hair products they wanted. We went to Brixton and bought them there!”

This included the Afro comb. With its longer teeth, usually spaced wider apart than a regular comb, it made it easier to, as Prof Tulloch explained: “fluff out the hair and help to give it more volume.” She added that this also made the Afro comb useful to white people with thick, naturally curly hair who had previously struggled to pull narrow-tooth combs through their locks. As counterculture became popular in the 1960s, Prof Tulloch noted that white people could also be seen with their hair in the Afro style, especially at festivals such as Woodstock.

But the Afro comb was not a 20th Century invention. Examples of it can be traced back thousands of years. A more recent design became popular during the 1970s, with the handle of the comb ending in the clenched fist that was the salute of the Black Power movement. This was first patented by two Americans - Samuel H Bundles Jr and Henry M Childrey - in 1969.

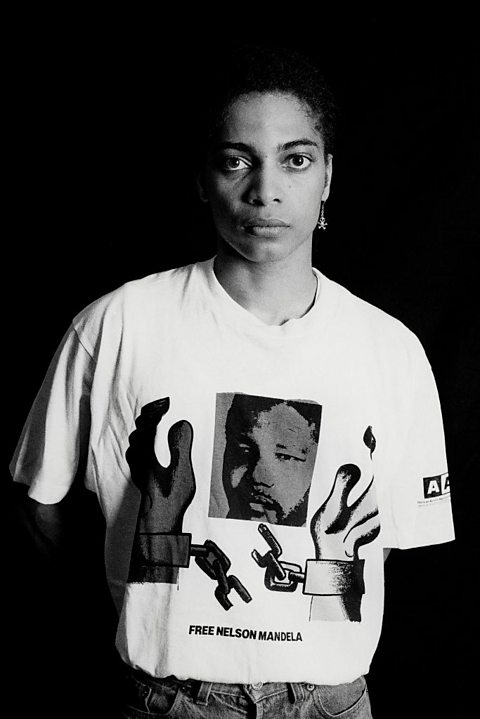

Protest t-shirts

Using the front of a t-shirt to express your views isn’t unique to black culture - it’s also been employed, for example, by groups campaigning for women’s rights and LGBTQ+ causes.

“It’s an activist tool,“ said Prof Tulloch, “as in Black Lives Matter, for example. It’s a form of making statements.”

In the 1980s, some countries - including the UK - boycotted goods and trade from South Africa due to its policy of apartheid, which favoured white people and gave them more rights, and saw them living separately to black people.

Protest groups, such as the Anti-Apartheid Enterprise, produced their own merchandise to spread the message about their cause. This led, as Prof Tulloch explained, to some mass-produced t-shirt designs becoming popular and worn by influential musicians and celebrities who also wanted to show that they opposed apartheid. She said: “It was a movement to release black people from apartheid in South Africa, but it was worn by both black and white people in the UK too.”

Apartheid officially came to an end in the early 1990s and Nelson Mandela was elected president of South Africa in 1994.

This article was published in October 2023.

Black History Month: Pioneers in British black history

Shining the spotlight on some of the inspirational black trailblazers in British history

Black History Month: Pioneers who became creative industry legends

They led the way in fashion, make-up and car design

Black History Month: A father and son share stories

Two generations talk about racism, inspirational figures and their lessons at school