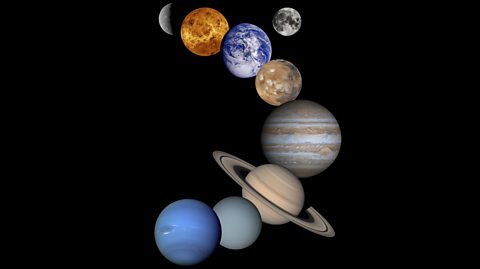

Everyone knows about the Solar System, and the planets that make it up. Theyâre in space, orbiting the Sun, in an order we all at least used to be able to recite.

But it was not always so. Until the likes of Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo came along, everyone thought the planets (that they knew about) revolved around Earth, and before even that, no one was really sure what those big bright things in the sky even were.

Thanks to thousands of years of observation, and careful study by some incredibly bright minds, we now have a good understanding of our Solar System. From the one with the ears, to the 11 year old girl that gave one of them their name, here are the stories behind each of the planets within it.

The first five

Apart from Earth, the five closest planets to the sun are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. They donât have discovery stories per se - they're visible to the naked eye, and so have always been seen by humans, but perhaps misidentified. They've been observed since prehistory, and have been of huge importance to countless human civilisations since. In fact, some say we have seven days a week because of these five planets, along with the Sun and Moon.

Dhara Patel, an astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, explains that theyâve been seen by people and civilisations since âantiquityâ, but that they were often mistaken for stars: âBabylonian astronomers actually were able to identify them as being notable objects in the sky, but when we look at them with our eyes, planets look like points of light - at the least the ones we can see.â

But these astronomers watched them over time, and discovered they moved in an entirely different way to stars. They would move across the sky where stars should appear to stay still, and so people started to suspect they they were something else entirely.

Mercury

Mercury is slightly different to the rest of the planets in this group. Being so close to the sun, so small, and so far away from Earth, itâs the hardest of the five to spot.

Pierre Gassendi was the first person to spot it moving in front of the Sun with a telescope in 1631, but he was only able to do so because it had been predicted earlier by Johannes Kepler. This observation led to a far deeper understanding of the planet - where before they were just just bright points of light, the telescope turned the planets, including Mercury, into worlds.

Venus

Venus is a different story altogether. It's much bigger and closer to Earth, but crucially its thick atmosphere reflects about three quarters of the sunlight that falls on it, so it's very bright and is fairly easy to spot with the naked eye. In fact, the Ancient Mayans had a particular interest in it - it was observed and documented by them as early as 650 BC.

âThey were quite keen on Venus as a particular planet, because of its regular appearance and disappearance,â Brian Sheen, director of the Roseland Observatory, explains.

However: "It took them quite a while before they realised it was the same planet in the morning as it was in the evening.â

The Mayans were extremely keen astronomers, and a lot of what they saw in the sky they linked with theories of spirituality. One such example Brian gives is how they perceived the afterlife: âThe Milky Way was described by the Mayans as the pathway to the dead.â

Galileo Galilei made an important discovery about Venus much later. He observed the planet not only waxing and waning through a telescope, but also appearing to change size. This showed him the planet was in fact in orbit around the Sun, and helped him gather evidence for one of the most fundamental theories about our Solar System (which we will come onto a bit later).

Mars

Mars is known for its bright red colour, and as Brian says, âitâs always been the planet of war.â The Egyptians called it âHer Desherâ, meaning the red one, and the Greeks called it Ares, after their god of war.

However, it wasnât the only red planet on the block, as Dhara explains: âMars was often spotted in a part of the sky where we find a star called Antares. And that's what Antares means; it means anti-Ares." The two can have a similar appearance in the sky, hence the need for the distinction.

The Romans had different names for the Greek gods, and so they were the ones to eventually call it Mars.

Jupiter

Jupiter is the biggest planet in our Solar System, and it gets its name from the leader of the ancient Roman gods.

Even though it had been observed in the sky since prehistory, it wasnât until Galileo came along with his trusty telescope that more was found out about it. In fact, what he saw surrounding the planet led to one of his most important discoveries.

Brian says that when Galileo put his telescope on Jupiter, he saw four tiny dots moving around the gas giant.

âThey were all in line with the equator of Jupiter they all moved round⊠in a regular manner." This showed Galileo something extremely important - that the planets could orbit things other than Earth.

The Polish mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus had theorised the Earth didnât in fact sit in the centre of the universe, with everything revolving around it, in 1543. With this observation of Jupiter, and earlier observations of Venus, Galileo was able to provide convincing evidence that Copernicus was right.

However, Brian says that âit didn't make him very popularâ, although that may be the understatement of the century - he was actually put under house arrest when he published works about the theory, as it had been deemed heresy by the Church!

Saturn

The oldest records of Saturn were made by the Assyrians in the Middle East around approximately 700 BC. They referred to it as the Star of Ninib, which means the Star of the Sun. The ancient Greeks also thought Saturn was a wandering star, and named it after their god of agriculture, Kronos. The ancient Romans later renamed it to reflect their god of agriculture: Saturn.

âSaturn is again something which Galileo looked at,â Brian says.

âHe described it as a planet with ears. Now, obviously he didn't believe they were physical ears. But he couldn't understand what they were. And how many people looking at Saturn today would say 'you idiot, why couldn't he see the rings?'â

Well, the answer to that is simply because his telescope wasn't good enough.

The last three

While the first five planets in the Solar System had been viewed by civilisations for millennia, the last three are essentially unobservable to the naked eye. That means that, not only do you need a telescope to see them clearly (and in Pluto's case, you need a powerful one), for a long time no one was aware they existed.

Uranus

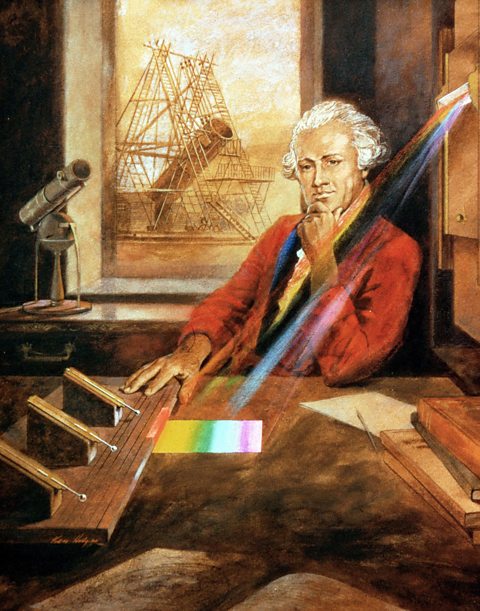

The discovery of Uranus is credited to an astronomer called William Herschel.

He was looking for comets in his back garden in Bath and he found something that, at first, seemed to behave like one.

Dhara explains that comets are relatively small âobjects that orbit around our sun, and they have very long orbits which means they are found further out in our solar system.â Given this distance and their pattern of movement, itâs easy to see how the mistake was made.

However he started to study its pattern of movement much more closely and noticed it was actually orbiting the Sun.

It was in about 1783 that Herschel was confident in his assessment that this was actually a planet: âHe noticed that because of its more circular orbit that it appeared to have, it was likely not to be a comet,â Dhara explains.

âComets tend to have more elliptical orbits which means they're more like squashed circles."

The shape of its orbit was what helped Herschel make his discovery.

Neptune

Neptuneâs discovery is closely linked to Uranusâ. After Uranus was discovered, a lot of time and effort went into studying it, and after a while, it was realised that something wasnât quite right: âIt wasn't moving in the way it should haveâ.

As Dhara explains, Uranusâ orbit was rather unusual: âat some point it was being sped up, and then afterwards, it was slowing down in its movement across the sky.â

One mathematician who theorised this was Mary Somerville, a mentor of Ada Lovelace. She wrote in 1836 that difficulties in calculating the position of Uranus may point to the existence of an undiscovered planet.

She was right - it was Neptune.

âUranus was being sped up by Neptune's gravitational pull.

âThere was a French mathematician called Urbain Le Verrier, and there was a mathematician from right here in the UK called John Couch Adams, and both of them separately had got the data of Uranus' movement in the sky. They had calculated where this perturbing object might be."

After both separately getting the data, it was then a race against the clock to see who would discover what was causing the mismatch. John Couch Adams actually wrote to the Astronomer Royal at the observatory in Greenwich, where Dhara works, to ask him if he would turn his telescope round a bit to point at where they theorised the new planet might be, but was denied his request: âGeorge Biddell Airy, the Royal Observatory's Astronomer Royal at the time, basically turned around to him and said no, it's not part of my work right now, so I'm not going to do that.â

At the same time, Le Verrier asked his friend at an observatory in Berlin to do the same thing. Perhaps they were better pals, but in any case his request was accepted and the astronomers in Berlin saw it with their own eyes. Le Verrier finally had proof that a new planet, later named Neptune, existed.

Apparently the Astronomer Royal, George Biddell Airy, never lived it down - we can see why!

Pluto

And finally, we have Pluto. It was controversially demoted to a dwarf planet in 2006, but it was first discovered in the 1930s, using photographic plates. Clyde Tombaugh at Lovell Observatory had taken two images of the sky about eight or nine days apart, and turned them into something of a flip book - going back and forth between them showed that something (which they later discovered to be Pluto) was changing position.

Pluto also has the honour of having the youngest ever person to name it - an 11 year old girl from Oxford called Venetia Burney suggested the name to her grandpa, who forwarded it to Lowell Observatory where it was eventually selected. Venetia actually got to see the planet the year before she died - it was the first time she had ever looked through a telescope, too!

Written with the help of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Ten things you didn't know about our Solar System

You'll be a star student once you've read this!

A beginner's guide to stargazing

How to get started with little to no equipment.

Five things we get wrong about space

Forget everything you thought you knew about space and read this.