Credit card

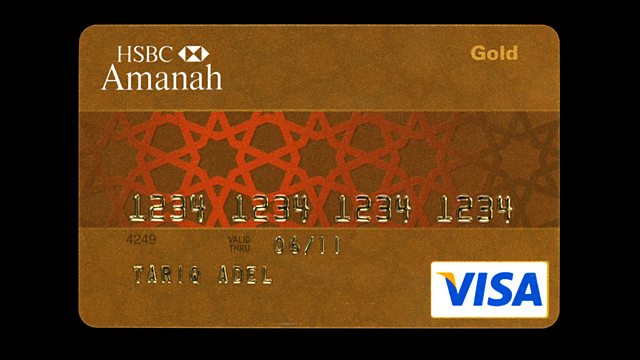

Neil MacGregor is looking at the forces shaping our modern world. Today he tells the story of the credit card for Muslims, one that is compliant with Sharia law.

Neil MacGregor's history of the world as told through things. Throughout this week he is examining objects that speak of the great shifts in human organisation and thinking in the modern world - objects that raise questions about human lives, the environment and global resources. So far this week he has chosen things that deal with political and sexual revolution and that confront the disaster of global arms proliferation. In today's episode he considers the morality of modern global finance and its implication for the future. He tells the story with a credit card that is compliant with Islamic Sharia law - what does that mean and how does it work? He talks to the Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, and to Razi Fakih of the HSBC bank.

Producer: Anthony Denselow

Last on

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects - objects related to money, trade and travel.

About this object

Location: Issued in United Arab Emirates

Culture: The Modern World

Period: 2000 - 2010

Material: Plastic

Ìý

This credit card exemplifies the global nature of modern finance. HSBC, originally founded in Hong Kong and Shanghai, created its Amanah division in 1998 to appeal to the growing financial hubs in the Middle East and Asia. Islamic law forbids exchanging money for profit and this card is Shari'a compliant, meaning that interest cannot be received on savings, or charged on borrowings. Shari'a compliant banks also cannot invest money in socially or morally damaging businesses and are mindful that Muslims must use their wealth to help the less fortunate.

When was the first plastic credit card created?

In the 20th century financial transactions in many western countries were increasingly no longer made in cash but through credit facilities, cheques and electronic money. The first credit card was the Diners Club Card, created by businessman Frank McNamara in 1950, after an occasion when he did not have enough cash to pay for dinner. Today, over fifty percent of all transactions in the USA and UK are made on plastic cards, although in the rest of the world cash is still used for the majority of purchases.

Did you know?

- The first person to use a cash machine in Britain was Reg Varney from popular sitcom On the Buses in 1967.

A validation of a promise to pay

By Mervyn King, Governor of the Bank of England

Ìý

I’d say it’s not a currency. This is a means by which an individual can obtain validation of his promise to pay. So that what the bank is doing is in a way helping the person who wants to sell something to the individual whose credit card that is, to validate that the person actually has the resources to meet the obligation to pay. So if you like it’s more like an I owe you, but where the ‘I’ is backed up by the word of the commercial bank that tells the ‘you’ that you can take the credit card because the person has resources to pay and will in fact do so.

This is one way in which using technology you can speed up the time in which when someone says, ‘Well I promise to pay you in the future’, you can somehow ensure that that will actually happen by using electronic payments. And it does mean that, in terms of the future, if everyone were able to make every transaction through a credit card, then would you actually need money in the conventional sense at all?

I think the ways in which the card is constructed is very much between the bank and the customer. And clearly the banks that have issued such cards have seen an advantage in setting up the transactions in a way that their customers will be more likely to accept. And of course the importance of this is that, as in all types of money or cards used to finance transactions, the acceptability, the trust which the other side of the transaction puts in it is paramount. If I could give a different example which I think illustrates the importance of trust here.

When Argentina had its financial collapse, and reneged on its national debt, in the 1990s, the currency became worthless. And in some of the villages of Argentina the use of IOUs as a substitute for paper currency started to grow up. But, the problem with the IOU is that the U has to trust the I. And that may not always be the case. So what happened was that in the villages some of them would take the IOU to the local priest and ask him to endorse it. And the priest, where he felt that he could judge the character of the person who was owing the money, making the promise, would do so, and the person receiving it would be confident that the person making that promise would certainly not want to renege on a promise that he had made to the local priest.

Now here we have an example in terms of the use of religion which was not fundamentally about religion as such, but which was about enhancing the trust that people had in the instrument that was being used.

Taking care of plastics

By Clare Ward and Joanne Dyer, Department of Conservation and Science, British Museum

Ìý

Many objects made recently contain plastic components and as museums start to collect them conservators are faced with the new challenge of taking care of these modern materials.

There is a wide range of different types of plastics and many are relatively stable. However some are inherently chemically unstable. This is probably because their purpose is ephemeral and they are not intended for long term survival.

Often plastics may be made to look like natural materials such as ivory, amber and tortoiseshell and so we often don’t know that they are present in an object until we study them more closely.

Most plastics deteriorate by reaction with oxygen - often in processes initiated by light and heat. The most unstable plastics are some of the early forms like cellulose nitrate and cellulose acetate, as well as polyvinylchloride (PVC) and polyurethane (often present as foam). Plastics such as cellulose nitrate and cellulose acetate deteriorate evolving acidic gases which can be damaging to the objects themselves and also other objects in the vicinity.

As they degrade surfaces start to craze and any associated metal components may start to corrode. PVC deteriorates by loss of plasticiser which is identifiable as a sticky layer on the surface of the plastic while polyurethane foam becomes brittle and crumbles.

So, the question is how do conservators look after objects made out of plastic?

Since plastics have different properties it is very important to recognise which plastics are present which we do using a technique such as infrared spectroscopy. In general the recommended conditions for the long term preservation of plastics are low temperatures to slow down chemical reactions and low light levels. Since plastics tend to become more brittle over time, supportive storage in the correct shape also helps.

As most credit cards have an operating lifespan of one to three years, none of these conservation issues should trouble the users. It’s just us museum conservators who have to worry about it!Ìý

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Thu 21 Oct 2010 09:45±«Óãtv Radio 4 FM

- Thu 21 Oct 2010 19:45±«Óãtv Radio 4

- Fri 22 Oct 2010 00:30±«Óãtv Radio 4

- Thu 18 Nov 2021 13:45±«Óãtv Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Money, Trade and Travel—A History of the World in 100 Objects

A History of the World in 100 Objects - objects related to money, trade and travel.

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects