Ants are better at socially distancing than us

In Radio 4's NatureBang, presenters Becky Ripley and Emily Knight like to find stuff from nature that will make your mind go "BANG".

With their brilliant box set now available on ±«Óãtv Sounds, Becky and Emily are here to bring you the three most fascinating things from the latest series, starting with ants...

1. Ants know how to fight a pandemic

If you want to know how best to survive the pandemic, why not take some tips from the experts? Nature’s ultimate epidemiologists – the humble garden ant.

Ants are very social creatures

All animals exist on a kind of social spectrum. From loners at one end (bears meet only to breed) to socialites on the other (mongooses live in close colonies and raise each other’s young). But the champions of the social scene are definitely the insects. Ants, bees, termites and wasps are what’s called "eusocial" animals – they’re so completely reliant on one another that they can’t survive alone. They build together, live together and they cooperate to raise the young and to fight off threats, sacrificing themselves if necessary for the good of the community.

The more social you are, the more you can rely on each other to help out. But it comes with a risk too – the risk of disease. You’re much more likely to catch infections from your pals, and to pass them on to others too.

So how do they avoid pandemics?

Scientists at the University of Bristol have been studying ant colonies to try and figure out how these super-social insects mitigate the risk of disease. And the answers are fascinating.

First, they have impeccable hygiene. They groom and clean one another on entering the nest to check for disease – in this case, a deadly fungal spore. No need for hand sanitiser for them: they spray formic acid from their mouths to thoroughly destroy any pathogens they find.

And second, ants that get sick play their part too – they take themselves away from the nest. In other words, they self-isolate. Sadly, for ants, infection is nearly always fatal, making this self-isolation the ultimate sacrifice.

Socially distancing, before it was cool

Finally, when infection is in the air, even ants that are NOT infected also steer clear. They spend more time out foraging for food, and less time in the nest, where they might become infected, or infect others. In other words, they use pre-emptive social distancing.

So next time you’re trying to make sense of the tier system or remember where you put your mask, think of the ant, and remember that for us, as well as them, it’s all about looking after one another.

2. Dogs poo facing north

If you have a dog, you might have noticed that they’re pretty good at finding their way about. And you’re not alone – humans have been collaborating with canny canine navigators for a very long time. Dogs are used for hunting and tracking, pulling sleds and search-and-rescue operations, all of which require top-notch navigational abilities.

How do dogs navigate?

It’s called Spontaneous Magnetic Alignment – they just like to line up.

Dogs have a number of tricks up their sleeves – they have a great sense of smell, strong eyesight and a good memory, all of which can help them find their way home. But that’s not the full picture. Dogs have another skill that’s fairly mind-blowing –

They can detect the magnetic field of the earth.

It’s called “magneto-reception”, and it works a little bit like an in-built biological compass. Dogs can feel the magnetic lines of flux that traverse our planet from pole to pole; they use this knowledge to position themselves in space, and work out what direction they need to go. And it’s not just dogs – many animals, from eels, turtles, homing pigeons, bats and even the humble fruit fly can do it too.

The compass test

So how can you tell if your pooch is detecting the magnetic field of the earth? Well, take a tip from the scientists – grab a compass, and watch them go for a poo.

Yep. You read that right.

One consequence of dogs being able to feel the magnetic tug of the poles, is that they seem to just prefer to face north, or south, if possible. It’s called Spontaneous Magnetic Alignment – they just like to line up. And one time when you can see them do it is when they stop to answer the call of nature.

The scientific poo study

If you feel silly standing compass in hand, watching your pup do a poo, spare a thought for the scientists of Barry University in Miami. Over two years, they followed dogs around on their daily walks and noted which way they faced as they answered the call. The study involved 70 different dogs, and a staggering amount of "business" – nearly seven-and-a-half THOUSAND defecations or urinations, enough data to prove that yes, dogs really do poo north… or south.

3. Slime mould can help map the universe

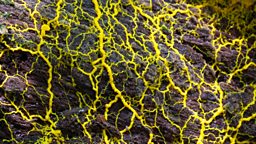

The slime mould algorithm produced a 3D map of the underlying cosmic web structure.

Slime mould looks like what it sounds like – a slimy mould. But it’s not actually a mould, it’s a protist – a giant single cell with many nuclei that divide as it grows. It forms large exploratory networks in search of food, finding near-optimal pathways to connect different locations.

The problem-solving cell

One species in particular is incredible at networking. It’s called Physarum Polycephalum and – in human terms – it is effectively able to “problem solve”, navigating systems and mazes with incredible efficiency.

Many experiments have been done using Physarum to model real-world problems such as urban transport networks, but it doesn’t stop there. A Physaram-inspired algorithm has also helped us to model the cosmos!

The problem with the cosmos is that most of it is invisible – consisting primarily of the mysterious substance known as dark matter and laced with strands of gas which, astrophysicists believe, bind together the galaxies of the universe. Enter slime mould, to help us imagine what this invisible web might look like.

The 3D map

Some scientists made a digital simulation plotting the locations of the 37,000 galaxies known to us. Then a Physarum-inspired algorithm (adapted from the petri dish to work in three dimensions) was left to virtually "feast" on this huge simulation.

From there, the algorithm produced a 3D map of the underlying cosmic web structure, visualising those largely invisible "binding" strands of gas. It was tested against the Hubble Space Telescope’s images that have caught glimpses of the web – and they found that everything largely matched up.

There seems to be an uncanny resemblance between the two networks – one crafted by biological evolution, the other by the primordial force of gravity. It’s humbling to think that a brainless single-cell organism is helping us to understand the largest structure in the universe.

More from Radio 4

-

![]()

NatureBang

Science meets storytelling with a philosophical twist.

-

![]()

Is your cat making you a bad driver?

And other weird questions raised by nature.

-

![]()

Eleven pawsome facts about dogs

Who's a good boy? We have the answer.

-

![]()

Seven marvellous animals we'll never see again

The stories of once thriving animals now wiped from the planet.