Seven emotions that no longer exist

We often think of emotions as being fixed and universal. Yet emotions vary from place to place (think of the uniquely German Schadenfreude, for example) and new emotions are being discovered all the time, as anyone who’s experienced a twinge of FOMO will know. What's more, emotions – and the way they are experienced, expressed and talked about – can change over time, too.

We spoke to Dr Sarah Chaney, an expert from the . Dr Chaney and her colleagues brought their fantastical Lost Emotions Machine to Radio 3’s Free Thinking Festival to teach people about the emotions of the past that can help us understand how we feel today.

Here are a few of our favourites.

1. Acedia

Acedia was a very specific emotion experienced by very specific men in the Middle Ages: monks living in monasteries. This emotion would often be brought on by a spiritual crisis. Those experiencing it would feel despair, listlessness, lethargy and above all would have an overwhelming desire to leave the holy life.

“Nowadays this might be labelled as something like depression," says Dr Chaney, “but acedia was very specifically bound up with spiritual crisis and life in a monastery.” It was presumably a source of concern for abbots, who despaired of the indolence that accompanied acedia.

Indeed, as time went on, the term “acedia” became more and more interchangeable with “sloth” – one of the Seven Deadly Sins.

2. Frenzy

“This is another good medieval emotion,” explains Dr Chaney. “It’s like anger, but it’s more specific than the way we use anger now. Someone experiencing frenzy would be very agitated. They’d have violent fits of rage, throwing themselves around and making lots of noise.”

Safe to say, it would be impossible to sit in a quiet frenzy. This emotion highlights our modern tendency to think of emotions as being essentially internal; something that you can hide, if you try hard enough. This simply didn’t apply to the people who experienced frenzy in medieval times.

“The language people used to describe their feelings meant that they felt things that we can never experience,” says Dr Chaney. Many historical emotions are so specific to their time and place that it’s impossible for us to experience them today.

3. Melancholy

Melancholy is a word that we use now to describe feelings of quiet sadness or pensiveness. “But in the past, melancholy was different,” says Dr Chaney. “In the early modern period, melancholy was thought of as a physical affliction that was often characterised by fear.”

Up until the 16th Century, health was believed to be influenced by the balance of four bodily humours: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. Melancholy would result when the person had too much black bile.

“One of the symptoms of melancholy back then was fear. In some cases, people were terrified to move because they thought they were made of glass and would break,” says Dr Chaney. King Charles VI of France famously shared this melancholic delusion and had iron rods sewn into his clothes to protect himself from accidental shattering.

4. Nostalgia

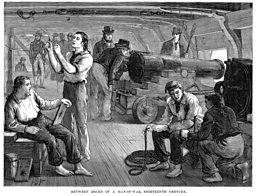

Nostalgia is another emotion you might think you already know. “We use the word ‘nostalgia’ quite freely in conversation now, but when it first came into use it referred to what was thought of as a physical disease,” says Dr Chaney. “It was an 18th-Century disease of sailors: something that happened when they were far from home, and was linked to a longing for home.”

Unlike modern nostalgia, 18th-Century nostalgia had physical symptoms. Nostalgic sailors would be tired, lethargic, suffer mysterious pains and be unable to work. A severe case of nostalgia could even lead to death. It doesn't really compare with our modern definition of nostalgia as a longing for the good old days.

5. Shell shock

Most people have heard of shell shock, a condition that affected soldiers in the trenches of World War I. Like melancholy, nostalgia and many other emotional experiences throughout history, shell shock trod a strange line between emotion and illness in the way in which it was talked about and treated.

“People suffering from shell shock had strange spasms and often lost their ability to see and hear, even though there didn’t appear to be anything physically wrong with them,” says Dr Chaney. “At the beginning of the war, they thought that these symptoms were caused by being close to explosions that physically shook the brain. But later on it was thought that all these symptoms were being caused by the patients’ experiences and their emotional state.”

6. Hypochondriasis

Hypochondriasis was another medical condition that by the 19th Century had acquired purely emotional associations. “It was basically the male version of what Victorian doctors called ‘hysteria’,” explains Dr Chaney. “It was thought to cause tiredness, pain and digestive problems. In the 17th and 18th Centuries, hypochondriasis was thought to be caused by the spleen, but later on it was blamed on the nerves.”

The Victorians believed that the symptoms were caused by hypochondriasis, or obsessive worrying about the body – so although physical symptoms were on show, it was the mind and the emotions that were believed to be ill.

7. Moral insanity

The term “moral insanity” was coined by the doctor James Cowles Prichard in 1835. “Effectively, it just means ‘emotional insanity’," says Dr Chaney, “because for a long time the word ‘moral’ meant ‘psychological’, ‘emotional’ and also, confusingly, ‘moral’ in the sense that we mean now.”

The patients Prichard deemed “morally insane” were those who acted unusually or erratically while having no sign of a mental disorder. “He felt there were a large number of patients who were able to function mostly like other people, but were maybe unable to control their emotions, or unexpectedly committed crimes,” says Dr Chaney.

Kleptomania in educated society ladies, for example, would be seen as a sign of moral insanity because the women were perceived as having no reason to steal. “It was basically a catch-all for extreme emotions, and was often applied to difficult children.”

We all know a few toddlers who could be described as "morally insane" on occasion…

Dr Sarah Chaney took the Machine of Lost Emotions to the Free Thinking Festival, which in 2019 is devoted to the theme of emotion. Browse all the fascinating talks and panel discussions from this year's event on the Free Thinking Festival website.

And don't forget to .

-

![]()

Free Thinking Festival 2019: Emotion

Browse all talks, panel discussions and articles from this year's festival.

-

![]()

The way we used to feel

Discover the clues we have to the emotional lives of Tudor royalty and what million-year-old human remains tell us about how prehistoric people felt.

-

![]()

Arts and Ideas podcast

Leading artists, writers and thinkers discuss the ideas shaping our lives and the links between our past and present.

-

![]()

The Essay

Insight, opinion and intellectual surprise - subscribe to the podcast now.