‘I didn’t know my father was a priest…’

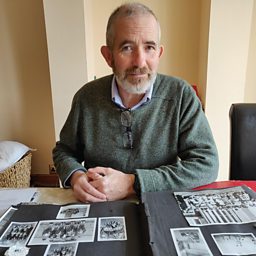

Michael McGuirk spent much of his childhood not knowing his father’s true identity.

He told his extraordinary story for the first time to Dan Tierney in Radio 4's Hidden Children of the Church.

Michael’s father was a Catholic priest – a chaplain to the Irish army at the time he met his mother, who was an army nurse.

“When she fell pregnant in 1950s Ireland,” he says, “it must have shaken her to the core… she went AWOL from the army and came to live in London.”

Around a year later his father also left to join his mother without telling anybody. Michael was still a babe in arms and his father struggled to earn a living owing to his age and lack of a CV.

What happened next has been pieced together by Michael and his family over a number of years.

A report in the News of the World from 1963 reveals how Michael McGuirk’s father had been supporting his family: “When Fr Bernard Joseph McGuirk fell in love with a pretty Irish nurse, he forsook the Church… the 49-year-old priest fell in bad company and took to crime. Now he's started an 18-month sentence, passed at the Old Bailey, for his part in a fraud and conspiracy which netted more than £5000 in five months." Michael’s father appealed his sentence and was released after 6 months. His family believed that he sinned less than he was sinned against.

Guidelines published in 2020 recommend that priests should leave the priesthood to look after their children.

The idea of his father keeping company with gangsters came as a mixture of shock, horror and mild amusement to Michael. His uncle once told him about a time his father confided in him: “He said, 'my boss carries a gun… not to shoot people who are coming at him, but to shoot himself if they were to come at him.'" The rival gang, it seems, were notorious for torturing people.

Meanwhile, his father’s religious order had tracked him down and persuaded him to re-commit to the priesthood. Following his release from prison, he was sent by his order to America, where he had the opportunity to wipe the slate clean. It was a decision that now leaves Michael cold: “My father was probably shell-shocked from the experience he’s had in prison and with violent criminals, so who could blame him for wanting to go back. But what I’m cross [about], is that the Catholic Church put such a huge distance between a father, the woman he loved and his child.”

Michael admits that this distancing contributed to mental health problems throughout his life. The story he was told as a child was that his father was a businessman, making his fortune in America, and that he would come back and they would all live happily ever after. That never happened. From then on, he saw him only fleetingly in the summer holidays.

The realisation that his father was a priest came slowly to Michael. He suspected the truth long before he was told. It was all unspoken. Over the years Michael and his father grew increasingly emotionally distant. He was a teenager when his mum told him the news of his father’s death. He didn’t shed a tear and he didn’t attend the funeral.

Despite his disrupted upbringing, Michael believes his parents did their best in difficult circumstances. A few years ago Michael visited his father’s grave in America for the first time: “I took some soil from my mother’s grave and I laid it on his grave; and I took soil from my father’s grave and I laid it on my mother’s grave. I wanted to say, 'Look Dad, it’s OK between you and me.'”

Michael is not so forgiving of the Catholic Church and the culture of secrecy that he believes precipitated the long sequence of painful events in his life. His story, it turns out, is one of thousands. After decades of denial, the Vatican has admitted there could be as many as 10,000 children of supposedly "celibate" priests living around the world. Guidelines published in 2020 recommend that, unless in exceptional circumstances, priests should leave the priesthood to look after their children.

Campaigners, however, believe priests will continue to have "hidden" children regardless of these new rules, and that unless the compulsory vow of celibacy is abolished, or the church becomes more lenient towards priests who father children, they will forever signify a broken vow.

For Michael, the answer lies in St John’s gospel: “The truth will set you free”; and he makes a simple plea: “I’d like all of the children of Catholic priests, on Father’s Day, to ask their local church to say a prayer for these priests and these mothers and these children who’ve been hidden away; to be open about it. Because that’s the only way that anybody can live with anything that they’ve done.”

-

![]()

Hidden Children of the Church

Three children of "celibate" priests describe childhoods separated from their fathers, shrouded in secrecy and shame.

-

![]()

Guns and rosaries...

Michael McGuirk speculates about who his father worked for.

-

![]()

Uncovering the truth

The moment Michael McGuirk knew his father was a priest.

-

![]()

Beyond Belief: Celibacy

Ernie Rea and guests debate how the role of celibacy differs among religious traditions.

-

![]()

What secrets do religions hold?

Tiffany Jenkins travels to Rome to The Vatican's Secret Archive.