Bill Murray: The man, the myth... the exhibition

23 November 2015

Bill Murray, the enigmatic star of Groundhog Day and Lost in Translation, has a new role, although he may not be aware of it. The artist Brian Griffiths has made the actor the focus of his new exhibition at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art. NATALIE BUSHE asks him about the state of Murray-ness.

Why Bill Murray? Brian Griffiths’ response is just as enigmatic as the Hollywood star: “Bill Murray is not so much inspiration as rich material, to be directed, laid out and persuaded to perform”. Soon Griffiths is in full flow: “A Murray-ness has been employed..."

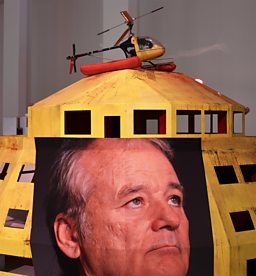

Bill Murray is authentic, he is a performer and this brings its own ambiguity. Griffiths has created a fantasy caricature of the actor, examining Murray-like uncertainties and ambiguities by constructing nine miniature houses. Each is emblazoned with Murray’s face or contains an object referencing the man or his work.

In the model of the whisky bar we are encouraged to imagine Murray at leisure – it’s Suntory time

All facets of the Murray are surveyed here, says Griffith:

“Bill Murray the man. Bill Murray the fiction. Bill Murray the object. Bill Murray the image. Bill Murray the hipster. Bill Murray the global superstar. Bill Murray the unique. Bill Murray the everyman”.

Thus the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man, which towers over the buildings of Manhattan in the film Ghostbusters, is replicated in a tiny comic conga of three Marshmallow Men. On the wall, Bill is banner-sized, decked out in plaid and playing to the Cannes Film Festival press corps.

While in miniature, the tartan theme is made manifest in a model of a Scottish mansion. And in its whisky bar we are encouraged to imagine Murray at leisure – it’s Suntory time.

Griffiths likes to play around with ideas of scale and we are asked to question how we experience and measure things. Level four of the Baltic is vast, and the miniatures are dwarfed further by their surroundings.

Being John Malkovich was in part an inquiry into the nature of personality, like Kafka on ecstasyBrian Griffiths

Griffiths says he wants to take us through “a metaphysical adventure story”, one in which the “scaled up and scaled down, detail and overview” are explored through the “slippery” disposition of Murray and the mutable quality of the man.

Objects are an obsession for Griffiths. Everything starts with collecting. When asked about his own remaking, reinvention and sometimes fabrication of materials Griffiths underlines what drives him.

“Collecting becomes a way of observing the world,” he says. “In a process of selecting and ordering , one can propose alternative perspectives, sensibilities or stories.

“I want an art that connects to my lived experience.”

For Griffiths, Bill Murray is his cultural object. I suggest to the artist that the exhibition, already loaded with cinematic reference, is reminiscent of the film Being John Malkovich. In this case, it’s a little window that opens into the mind of Murray.

“Being John Malkovich was in part an inquiry into the nature of personality, and a comment on the way we invest our own desires into things, like Kafka on ecstasy.

“John becomes a celebrity ripe for hollowing out into a blank receptacle.”

It’s a theme Griffiths has explored before in his Bear Head work for British Arts Show 7. For him, objects are a cipher through which we can talk about ourselves.

Popular culture and larger than life screen characters seem to appeal to Griffiths. He has form for using actors’ images in his work. He made 12 plaster character face masks of the sinister Peter Lorre in his work ‘Peter Lorre Time Machines’.

He also cites characters like Willy Wonka, used in his installation ‘When Few were Charmed’, and Rising Damp’s Rigsby among his inspirations.

For me, good art is felt like a side-splitting gagBrian Griffiths

Like those characters, Griffiths mixes overblown theatricality and pathos with wit and invention. For him Wonka embodies “the possibilities to imagine,” and “a sharp cultural critical tongue”.

Griffiths says insight lies in “Rigsby dreaming of being more, and the tragic sadness of watching this”.

Asked if humour makes art more appealing and therefore more accessible, Griffiths is surprisingly blunt.

“I do not use humour to make the work more appealing or accessible,” he says.

“It may do this. Jokes are playing with ideas. They deal in collective understanding and the contemporary situation. I believe art should do this. For me, good art is felt like a side-splitting gag.”

Griffiths also believes that art should ask questions. So what is the underlying question in Bill Murray: A story of Distance, Size and Sincerity?

“There are reccurring questions on our relations with the material and social world,” he says.

“How we use objects to create meaning, to make and re-make ourselves, to organise our anxieties and affections, to sublimate our fears and shape our fantasies.

“Questions of scale’s relationship to excess, over-desire and emptiness. Questions of why has Bill got such a watchable face?”

Any funny stories about Bill you can share with us?

“No funny stories but a bit of advice from Bill: ‘Grab this day by the neck and kiss it’.”

is at Level 4 Gallery, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead until 28 February 2016.

Related Links

More from ±«Óãtv Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms