Broadcasting may help to show that mankind is a unity.

WARNING: Some scenes in this video may be upsetting. They reflect the time when made.

âBroadcasting may help to show that mankind is a unity,â wrote John Reith, the ±«Óătvâs first Managing Director (later Director-General) in 1924, only two years after the ±«Óătv began. He quickly grasped that broadcasting would be life-changing, that it could bring people together in utterly new ways. But it did reflect a British perspective of its time that is essentially white and hierarchical.

Popular entertainers

There were non-white voices on the ±«Óătvâs first airwaves. As early as 1933, Britainâs first black star Elisabeth Welch sang her trademark song Stormy Weather on ±«Óătv radio and was a regular fixture there. The likes of Ken âSnakehipsâ Johnson was also a huge hit for popular music fans of the day, before his untimely death at the CafĂ© de Paris in the 1941 Blitz. ±«Óătv Televisionâs opening night in 1936 would also feature the popular Buck and Bubbles, an African-American duo of dancer-singers.

This tradition of the black entertainer would continue throughout the decades. It culminated in The Black and White Minstrels, arguably the ±«Óătvâs most glaring failure to understand the toxicity of stereotyping. The programme, which started in 1958, continued to command huge audiences of around 16 million before it was removed from the TV schedule in 1978.

Unique internationalism

In parallel, the ±«Óătv World Service was creating an international community of non-British voices at the Corporation. During WWII, it would expand from eight to 48 languages, instigating a rare cross-fertilisation of cultures.

Una Marson, the ±«Óătvâs first black female producer, was part of this, giving a platform to hitherto unheard Caribbean voices right at the start of the 1940s. But what would change everything would be the end of colonial rule â when new ethnic communities would make their way to Britain, transforming its social makeup. How would broadcasting react?

In Focus...

-

Una Marson

The ±«Óătv's first black radio producer -

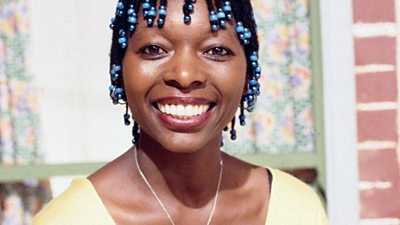

Floella Benjamin

The woman who changed childrenâs television -

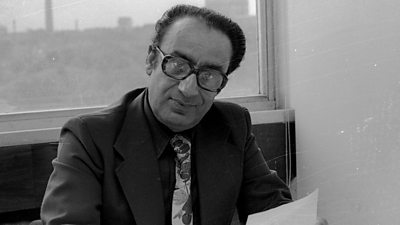

Mahendra Kaul

One of the first Asian television presenters

Pioneers

There were some pioneering moments. Drama, for example, showcased the tensions and inequalities that surfaced. A Man from the Sun (1956) told the story of West Indians in London: their struggle in the face of white prejudice and their own growing disillusionment. While Fable (1961) dramatically reversed African apartheid, putting black people in power and relegating white to the role of the subservient. Documentaries too challenged the status quo, asking the provocative question Has Britain a Colour Bar? in 1955.

The ±«Óătv would also create broadcast services catering specially for these new audiences. It may be easy now to mock In Logon Se Miliye then Apna Hi Ghar Samajhiye, roughly translated as Make Yourself at ±«Óătv (1965), with its tips on how to use a light switch and how to cook a British Sunday roast. However, its intention was to provide a much-needed platform for the new communities of British Asians, and its aim was firmly "to help in integration, not assimilation".

But the debate over integration or separation would continue. For example, when the ±«Óătv announced its decision to remove the Asian Network in 2010, it was obliged to reverse that decision because of the strength of reaction from Asian listeners who wanted a dedicated service.

Towards the mainstream

In the sixties, the ±«Óătv did remain predominantly white but times were changing. ±«Óătv Childrenâs first black presenter Paul Danqua (1964) would be followed by the likes of Derek Griffiths and Floella Benjamin. The latter went on to have a long career in advocacy and campaigning for racial equality, ending up with a seat in the House of Lords.

Trevor MacDonald began his career at the ±«Óătv and Moira Stuart became the first black woman to read the news in 1981. Alex Pascall fronted Black Londoners on ±«Óătv Radio London in 1974, later to become the first black daily radio show in mainstream British broadcasting. He would also go on to co-found The Voice, Britainâs first black newspaper. People from different ethnic backgrounds were now informing and educating, as well as entertaining.

From the nineties onwards, there was a shift in ±«Óătv mainstream programming, which featured more black, Asian and ethnic minorities across its schedule - from Goodness Gracious Me and Citizen Khan to Doctor Who and the Today Programme.

However, behind the camera or microphone was a different matter. In 2001 Director-General Greg Dyke made his famous statement that ±«Óătv management was âhideously whiteâ, and not till that changed could the ±«Óătv properly reflect the increasing diversity of the UK. The last two decades have seen a shift towards improving that, as well as increasing overall diversity across the whole ±«Óătv workforce, but the challenge is ongoing.

At the start of a new decade the ±«Óătv opens a new chapter with Creative Diversity â yet again shifting the paradigm to refocus the ±«Óătvâs DNA so it is more representative of the whole UK and of the wider world.