History is full of traitors and faithfuls, and a lot of people who were somewhere in the middle.

But sometimes, the decisions of individuals to turn their back on someone or something, had a significant effect on history.

±«Óătv Bitesize has taken a look at three acts of betrayal which helped bring down a medieval king, killed a popular Roman leader and very nearly weakened the United States in its war against the British.

Julius Caesar: Beware the Ides of March!

The deadly betrayal of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44BC changed the course of Roman history. Thanks to William Shakespeare, that day shall forever be associated with the phrase âBeware the Ides of Marchâ, a warning to be wary of those around you (the Ides of March refers to the 74th day of the Roman calendar, 15 March). More recently, the character of Gretchen in Mean Girls (2004) uses the historical figures of Caesar and Marcus Brutus as a metaphor for high school girl in-fighting.

Julius Caesar was a military general and statesman who rose to the most prominent position in the Roman Republic. So great was his power that in early 44BC, he was able to declare himself dictator for life. Theoretically, this meant that he could go unchallenged and govern alone. His political rivals feared that he was becoming too powerful and began to plot against him.

Three of the ringleaders were Marcus Junius Brutus, Gaius Cassius Longinus and Decimus Junius Brutus, all ââAppointed political leaders in the Roman governing assembly.. Decimus Brutus had been close to Caesar, and was thought to be his second choice of heir. Marcus Brutus meanwhile, had opposed Caesar previously, fighting against him at the battle of Pharsalus in 48BC. However, Caesar had since pardoned and promoted him.

Together with around 60 other co-conspirators, they cornered Caesar in Romeâs Senate House and killed him. We donât know what Caesarâs last words were, but Shakespeare chose to emphasise the depth of betrayal in his choice of line for his historical play. The character Julius Caesar says âEt tu, Brutus?â, meaning âAnd you, Brutus?â, towards Marcus Brutus, highlighting that he didnât expect to be betrayed by someone he had forgiven and thought a friend.

Unfortunately for the plotters, they hadnât reckoned with just how popular Caesar was with the general public. When they announced his death from Romeâs Capitoline Hill, the reaction of the crowd was initially muted, before turning to anger and eventually violence. Marcus Brutus, Decimus Brutus and Cassius were forced to flee the city.

Julius Caesarâs death marked the beginning of the end of the Roman Republic, as his nominated heir, Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus/Octavian, ultimately became the first Emperor of Rome.

Isabella of France: The rebel queen

While it wasnât until the 16th Century that the UK got its first ââA woman who has inherited the crown in her own right, rather than via marriage., female monarchs were leaving their mark on history long before then. One of those women was Isabella of France, sometimes referred to as the âShe-Wolf of Franceâ, who played a significant role in the downfall of King Edward II of England in 1327.

The daughter of King Philip IV the Fair of France, she was born in the early 1290s and was married to Edward on January 25, 1308. Edward was known for having favourites among his nobles, first Piers Gaveston (captured and executed in June 1312 by nobles who resented him) and then Hugh Despenser the Younger.

When Edward declared war on Isabellaâs brother Charles IV of France in 1324, Despenser accused her of being a foreign spy, confiscated her lands and limited her ability to see her husband. However, Edward was still willing to send her to France to successfully negotiate a peace treatment with her brother. Edward himself also needed to visit France in order to pay homage to Charles IV for his French land holdings. However, he was unwilling to leave England given the threat of rebellion against himself and Despenser.

Instead, he made the mistake of sending his young son and heir, the future Edward III. Isabella now found herself in the protection of her brotherâs court, reunited with her son. From this strong position, she offered the king an ultimatum: Isabella and the young Edward would only return if Despenser was removed from court and her status and her land was restored. Edward refused to distance himself from Despenser.

Isabella allied herself with Roger Mortimer, an English nobleman-in-exile who had escaped the Tower of London after being imprisoned for his involvement in a rebellion against the king and Despenser. Together, they plotted to invade England and overthrow the duo.

With money, soldiers and supplies provided by the Count of Hainault (modern-day Belgium), they landed in England on 24 September 1326. King Edwardâs support faded quickly, and his powerful half-brothers and cousin joined Isabellaâs cause. Hugh Despenser was captured and executed, while Edward was forced to abdicate the throne in favour of his 14-year old-son. Later that year, he was mysteriously murdered at Berkeley Castle.

Coincidentally, Edward IIIâs reign began on his feuding parentsâ 19th wedding anniversary, 25 January 1327.

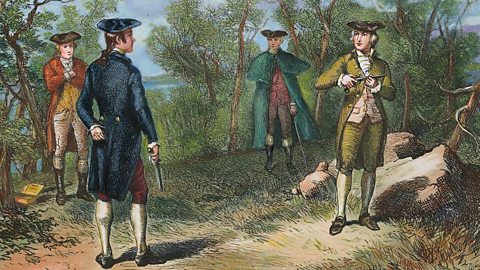

Benedict Arnold: Americaâs notorious traitor

In the US, the name Benedict Arnold is synonymous with betrayal. Once one of George Washingtonâs most talented field marshals, he helped guide the ââThe army set up to fight on behalf of the thirteen colonies, under George Washington, during the American War of Independence to their first victory of the American War of Independence at Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775. He would have further success at the 1777 Battle of Saratoga, which marked a turning point in the war and encouraged the French to ally with the revolutionaries. But all that would be tarnished a few years later when Arnold turned his back on the Americans and began to spy for the British.

Arnold felt that his achievements had been insufficiently rewarded, that others took credit for his tactics and that he had been passed over for promotion. His debts were beginning to climb as a result of his wifeâs lavish spending and he was rebuked by Washington on accusations of misconduct. Resentful, bitter and in need of money, Arnold reached an agreement with the British.

When Washington offered him an Army commander position in 1780, Arnold instead pushed for control of the defences at West Point, New York, along the Hudson River. This was a site of strategic importance for communication and transport in and out of New England. He planned to weaken the defences and hand over the area to the British in return for ÂŁ20,000, with the possible added bonus of luring Washington towards the enemy.

Arnoldâs betrayal was discovered when the British intelligence contact he was communicating with was captured, and incriminating documents were found. He managed to flee to the British warship HMS Vulture, was awarded a commission as a brigadier general and began fighting against his former comrades. Arnold survived the war, moved to England and died there in 1801.

This article was published in January 2024

Three famous feuding families in history

These feuding families took sibling squabbles and parental disapproval to a whole new level.

The tricky kings and queens quiz

Test your knowledge of the kings and queens of the British Isles with this fiendishly difficult quiz from ±«Óătv Bitesize.

Digging into the history behind Hamilton

Slavery, the 1800 election and Angelica Schuyler.